The concept of a ‘universal basic income’ – giving all citizens of a city, state, or nation a constant, guaranteed income – is gaining popularity.

The idea enjoys support far and wide, from tech CEOs like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk to political figures like Andrew Yang and Bernie Sanders. Andrew Yang headlined his 2020 presidential campaign with the Freedom Dividend policy, a $1,000 per month payment to every American over the age of 18. Even conservatives, who tend to condemn welfare programs on the grounds that they discourage work and/or increase the size of government, can find reasons to support UBI in that it could shrink the size of government bureaucracy involved in administering current ‘needs-based’ welfare programs.

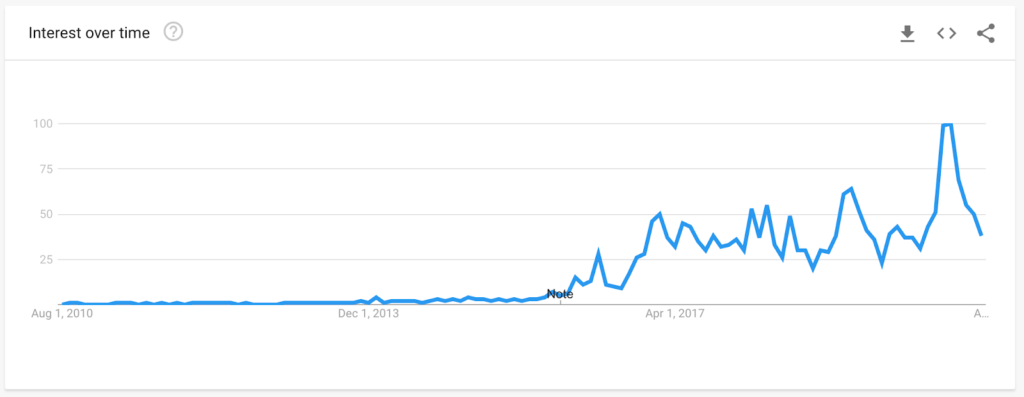

The economic crisis and massive unemployment triggered by lockdowns around the world led to a massive surge in interest in the concept. Governments opened the door for more discussion on universal basic income by distributing one-time ‘stimulus’ checks to citizens – most notably in the United States. One proposal from Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, known as the Automatic BOOST to Communities Act, would provide every American with $2,000 per month during the current crisis and $1,000 per month afterward.

A Global Idea

Universal basic income is a truly global idea as well – with Google searches on the concept coming from most developed countries. Many governments are experimenting with the idea, even running small-scale trials to learn more about potential effects of a UBI on the recipients’ behavior. Canada, Finland, Namibia, Kenya, and even states within the USA have run small-scale universal basic income trials. Iran has run a nationwide ‘unconditional cash transfer’ system since 2011.

Why UBI?

Proponents of UBI say the policy would reduce poverty by providing a safety net, just like welfare programs. However, this safety net would not be conditional, requiring what are known as ‘needs’ tests, reducing the administrative cost of a UBI program versus existing welfare programs. The extra income would reduce financial stress for many families and allow people to take more entrepreneurial risks – like starting their own businesses or focusing on nurturing their passions.

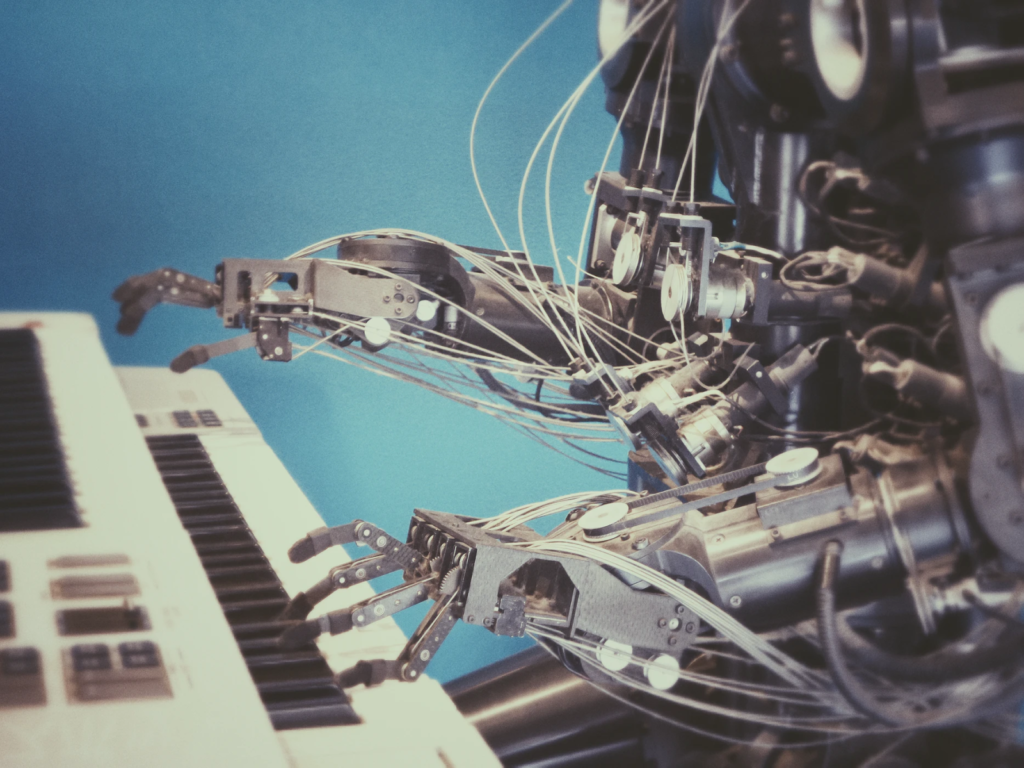

UBI is also proposed as a solution to a perceived threat to employment itself from automation. The belief by politicians and technologists such as Andrew Yang and Elon Musk is that a coming wave of automation will drastically reduce the number of jobs available to people, without a compensating growth in new employment opportunities as we’ve seen in past technological revolutions.

Finally, UBI could reduce the prevalence of strange incentives that arise from a needs-based welfare system – like people begging to be fired so they can collect unemployment checks, because those checks are worth more than their salary.

In this post, I want to focus on the ways that we could fund a universal basic income. As I’ll get into at the end of the post, proper funding for a universal basic income program is critical. Despite what Modern Monetary Theorists try to cook up, money does not grow on trees – there will always be a need to limit the supply of money or ‘soak up’ excess liquidity in the system. This is why taxes are still necessary, even in a world where governments can print currency to pay for things.

Let’s look at what a universal basic income would add to a government’s costs, and then walk through some ways to raise that money or cut it from other spending.

The Cost of Universal Basic Income

To understand the level of additional revenue a government would need to balance out a UBI program, we need an accurate read on the potential costs of the program itself.

A simple way to estimate the additional cost to a government from UBI is to multiply the annual payments by the number of citizens. For instance, a tax-exempt $1,000 per month payment to all 255 million Americans over 18 would cost 3.06 trillion dollars for the US government.

To give a consistent yardstick across countries, we can look at poverty lines from the World Bank. This organization groups countries into 4 buckets, and gives median poverty lines for each. I’ve also included the USA, which has a significantly higher poverty line than even the high-income countries median poverty line.

| Country Bucket | Poverty Line (annual income) | Example Countries |

| Low Income | $697 | Afghanistan, Uganda, Haiti |

| Lower-Middle Income | $1,172 | India, Philippines, Egypt |

| Upper-Middle Income | $2,000 | Argentina, Brazil, China |

| High Income | $7,920 | Australia, Italy, Saudi Arabia |

| USA | $12,140 | — |

A universal basic income aimed at alleviating poverty could be set at that poverty line – Andrew Yang’s Freedom Dividend proposed exactly this with $1,000 per month cash payments to American adults.

Let’s look at a few major nations, using these media poverty lines, to estimate costs of UBI programs around the world:

| Country | Population over 18 | Total Annual Cost of UBI Program | Cost as % of GDP |

| Haiti | 6,900,000 | $4.81 Billion | 57% |

| India | 927,000,000 | $1.08 Trillion | 40.7% |

| Brazil | 157,000,000 | $314 Billion | 15% |

| Australia | 19,500,000 | $154 Billion | 11.6% |

| USA | 255,000,000 | $3.06 Trillion | 16% |

The total cost for a UBI program varies heavily with the wealth of a nation and its total adult population who would receive benefits. However, this gives us a starting point for evaluating possible ways to fund a UBI program, and some perspective on how challenging or not it may be to raise the necessary funds.

Some UBI proponents argue that the policy would increase employment and prosperity, driving increased tax revenues without any change to the tax structure. However, these are unconfirmed speculations without strong numbers to back them, so we will stick to a more rigorous cost estimation for the purposes of this post.

12 Ways to Pay for a Universal Basic Income

To pay for a universal basic income, a nation either has to save that money elsewhere or raise it through additional tax revenue, new taxes, or new services. To fund a basic income at the poverty line in the USA, roughly $12,000 per American adult per year, means finding about $3 trillion annually. Let’s look at a few options.

$3.06 Trillion

Needed to fund an American Universal Basic Income

Canceling Existing Anti-Poverty Programs

By providing an income at the poverty line to all adult Americans, a universal basic income would hopefully eliminate the need for many existing anti-poverty programs. Two periods in American history led to large-scale anti-poverty programs: The New Deal following the Great Depression, and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society efforts during the 1960s.

Many programs installed during the New Deal continue in some form today: Social Security, food stamps (now SNAP – Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), the Federal Housing Authority, and Aid to Dependent Children (now TANF – Temporary Assistance for Needy Families). The Great Society programs included Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, and the Job Corps. Both of these eras expanded federal powers to provide support to individuals and set a precedent for further federal intervention.

A universal basic income would render many of these programs obsolete, as they would trade a needs-based approach for a far simpler citizenship-based approach. Each of these programs has a cost in the funds it disburses, but it also has a cost in terms of administration. Welfare programs are needs-based, meaning there are tests that an applicant must pass in order to be eligible for assistance through the program. For example, to qualify for CalFresh food assistance in California, the applicant must demonstrate their income is below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level – in 2020, that’s $2,024 in monthly income for a single individual.

The reporting, screening, and upkeep process to enforce restrictions on welfare recipients takes people’s time and effort, costing wages to government employees – money which could be spent directly on needy people. However, the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that, at its highest, federal programs are spending only 10% of their budget on administration costs – the rest is going directly to paying for services or direct cash transfers.

Determining the full cost of anti-poverty programs is a tall task, given the programs are spread across 10+ departments and over 100 individual programs at the US federal level, notwithstanding additional spending by state governments. To get a complete read on the cost breakdown of these programs, we can dive into the White House Office of Management and Budget 1,400 page report and mine the relevant data. However, the Congressional Research Service thankfully publishes a report titled Federal Benefits and Services for People with Low Income which gives a shorter, if less detailed, read on the total cost of welfare programs. The most recent year this report covers is 2016, so we’ll use those figures.

| Category | Spending in 2016 |

| Health Care (mostly Medicaid) | $467,829,000,000 |

| Cash Aid | $159,394,000,000 |

| Food Aid | $100,683,000,000 |

| Housing | $46,320,000,000 |

| Education | $53,729,000,000 |

| Social Services | $39,395,000,000 |

| Employment and Training | $6,534,000,000 |

| Total | $877,526,000,000 |

We can also add an estimate of state spending on anti-poverty programs, although these would not necessarily be eliminated if the federal government decided to swap spending on federal anti-poverty programs for a universal basic income. The Urban Institute estimates state spending on welfare at around $673 billion annually, however, $438 billion (65%) is financed by federal grants, so it’s already counted above. That leaves $235 billion in total spending on welfare by US states. Add that to the federal spending number, and you see how much could be saved by eliminating existing anti-poverty programs and replacing them with a universal basic income.

| $1.112 Trillion | 36% |

|---|---|

| Saved by Eliminating Anti-Poverty Programs | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

Importantly, this does not cover Medicare or Social Security – two of the most expensive assistance programs in the United States – since these are not purely anti-poverty programs aimed at needy people of all ages. These will be covered in a later section.

Canceling Healthcare Subsidies

The US federal government spent about $1.15 trillion in 2019 on healthcare expenses through programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and veterans’ care according to the Tax Policy Center. Medicaid alone makes up about 50% of anti-poverty spending at the federal level, according to researchers at the University of Michigan.

Other nations may find even more savings here, such as those with socialized healthcare systems. Take France for example, where health spending is $5,370 per capita (~11% of GDP), which seems low versus the United States’ shockingly high $11,072 per capita (~17% of GDP). However, approximately 77% of health expenditures in France are funded by the government, or $4,135 per capita – 8.5% of GDP. Compare that with the US government’s share of health expenditures, which is about 34% – leading to a cost of $3,765 per capita – 6% of GDP. France, while spending less per capita in healthcare overall, has relatively more government budget to cut from healthcare to fund a universal basic income.

Proponents of universal healthcare systems argue that socialized medicine lowers the cost of healthcare overall – the United States being a prime example of a broken privatized healthcare system. It’s out of the scope of this post to dive deeper into this argument – the purpose of this post is simply to highlight different budget line items and how they could add up to fund a universal basic income. A UBI system could also lower healthcare costs overall by reducing financial stress, a common underlying cause or contributor to many health problems as stated in over 200 studies.

Healthcare expenditures in the United States break down as follows:

| Category | Spending in 2019 |

| Medicare | $644 billion |

| Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) | $427 billion |

| Veteran’s Care | $80 billion |

| Total | $1.151 trillion |

| $1.151 Trillion | 38% |

|---|---|

| Saved by Eliminating Healthcare Subsidies | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

Cut Military Spending

Military spending has long been derided as an excess that many developed nations, especially the United States, could cut back in. The US government alone spent 3.29% of the country’s entire GDP on military in 2016. Russia and Israel spent over 5% of their GDP on military, but the world average is only 2.22%. Most of US spending goes to the base budget for the Department of Defense, which funds initiatives from warplanes to cybersecurity to wages for civilian DoD employees and soldiers alike. The total budget requested for the DoD for 2021 is $636.4 billion, plus $69 billion for ongoing ‘Overseas Contingency Operations’ – wars.

There is also the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Homeland Security, the State Department, nuclear energy projects and the FBI and Cybersecurity divisions. Those total another $228 billion in spending.

Cutting the entire budget may be disastrous – provoking attacks on US interests abroad, possibly, but even just in economic effects, as the Department of Defense is the nation’s largest employer. 1.4 million active servicepeople and 718,000 civilian workers. A 2019 breakdown of the military budget in the US noted $155.8 billion goes to military personnel accounts – if we take this figure out of the total military budget, we get around $777.6 billion.

| $777 Billion | 25% |

|---|---|

| Saved by eliminating military spending (all but personnel costs) | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

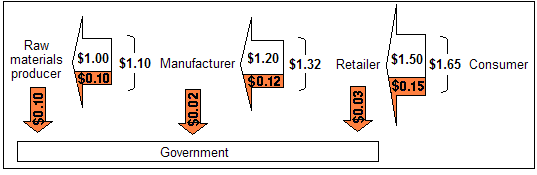

Value-Added Tax (VAT Tax)

A value-added tax adds a small tax to a product each time ‘value is added’ through the supply chain. A VAT tax differs from a sales tax in that producers pay some of the tax throughout the production process. If the entire VAT is passed on to the consumer through increased prices, then the consumer ends up bearing the brunt of the tax.

However, businesses must price competitively, so situations do arise where not all of the tax is passed on to the consumers – meaning businesses pay some of it. The IMF estimates that only 30-40% of a VAT tax is actually passed on to consumers, meaning businesses do end up shouldering the majority of the tax burden.

How could this increase tax revenues and pay for a universal basic income? First, the mechanics of a VAT make tax evasion more difficult, since a retailer who tries not to pay sales tax on sold items will still have to pay the increased price for goods and services (due to VAT tax) from their suppliers. Second, instituting a VAT significantly higher than the current sales tax could add taxes to businesses without affecting consumers – since about 60%-70% of the tax is estimated to fall on businesses. With sales taxes in the United States around 5%-10% depending on the state and city, a national VAT tax around 20% (as is common in many European countries) could bring in significantly more revenue.

With American consumption at around $17 trillion (yes, we Americans love our flatscreen TVs), a VAT tax of 15% would raise $2.55 trillion.

This is not to say a VAT tax would be politically feasible or beneficial to the economy. US states make an average of 12% of their revenue from sales tax, but in order to avoid end-consumer prices rising appreciably, the VAT would likely need to replace these taxes and eliminate an important source of funding for states. A VAT would also put new strains on businesses. Large businesses like Amazon and Google will easily be able to raise a 20 person team dedicated to accounting for, paying, (and let’s be honest – skirting as much as legally possible), for the VAT. Small businesses and those with tight margins (think corner stores and restaurants), however, will be saddled with accounting headaches and new expenses that could put them out of business.

For the purposes of this post, however, we just want to estimate the amount a VAT could raise.

| $2.55 Trillion | 83% |

|---|---|

| Potential additional revenue from a 15% VAT tax levied on all goods sold. | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

Financial Transaction Tax

A financial transaction tax would collect a small amount from every trade made in the financial markets. Former US Presidential candidate Andrew Yang proposed a 0.1% tax, saying it would raise $50 billion per year. Other former candidates such as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders also supported this type of tax, estimating it could raise anywhere from $800 billion to $2.4 trillion.

A financial transaction tax today exists in several countries with very developed financial markets, such as the United Kingdom and Hong Kong. To create an estimate of the amount this tax would raise, we need to estimate the impact on total financial transactions on US stock markets – since a tax will undoubtedly reduce trading volume as it has done in many other nations. The Brookings Institute crunched the numbers, and gave an estimate of around $200 billion for a financial transaction tax of 0.1% levied on all equities and options trading. Higher rates can push that number near and above $1 trillion, but the Brookings paper outlines several hidden risk factors and behavioral unknowns that make such a number unlikely.

| $200 Billion | 6.5% |

|---|---|

| Potential additional revenue from a 0.1% tax on all equity and options financial transactions. | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

Wealth Tax

A wealth tax is a persistent tax on all assets a person holds. Many Democrats in the US support this idea, saying it would fight inequality and raise revenue for the government. Combined with a universal basic income, this tax would essentially serve to redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor – by taxing the wealthy more than they earn from the UBI, and handing the excess to those with less wealth.

During her presidential campaign, Senator Elizabeth Warren proposed a 2% to 6% annual tax on wealth, depending on a household’s net wealth. The Tax Foundation estimates this could raise about $2.2 trillion.

However, it is worth noting that many European nations implemented a wealth tax since the 1990s but repealed it soon after. Reasons included “limited revenue collection, administration and compliance cost, tax avoidance, and evasion” according to the Tax Foundation. One such problem is a wealth tax would incentivize further ‘offshoring’ of assets like we saw revealed in the Panama Papers scandal. In order to avoid taxes, wealthy individuals use companies in tax-free jurisdictions to hold their assets. This is a common practice in the US, where many affluent people take advantage of just the corporate structure alone to protect assets from personal income taxes, which are often higher than corporate taxes.

| $2.2 Trillion | 72% |

|---|---|

| Potential additional revenue from a wealth tax of 2% – 6% on households with over $50 million in assets. | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

Eliminate Many Tax Breaks

Tax breaks, or ‘tax expenditures’ as the US government calls them, add up quickly. While 86% of government revenue lost to tax breaks is given to individuals, the 14% from corporations comes almost solely from one break – the deferral of taxes on income earned overseas through foreign subsidiaries and affiliates. This is the break that allows companies like Apple to avoid paying taxes for revenue earned on overseas sales by funneling proceeds through companies in jurisdictions like Ireland, which have very low corporate taxes.

While tax breaks theoretically exist to promote certain behaviors, they create additional complexity which benefits those who have the time (or money) to fully understand the tax code (or pay someone else to do it for them). Tax expenditures add up to $1.335 trillion, a massive figure when we consider that military spending is just shy of $1 trillion.

Eliminating tax breaks would not be without its unintended effects, however, that could damage the goals many supporters of universal basic income are striving for. For example, the tax break given for employer-paid health care and health insurance, which helps many families better afford care, is the largest single tax break at $143.8 billion in 2016.

| $1.335 Trillion | 43.6% |

|---|---|

| Eliminating all tax expenditures (breaks) | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

Nationalize or Tax a Resource

This one would be a stretch, politically, but could be a major source of revenue for the government. Nationalizing a resource means that the government takes over the extraction and sale of a natural resource from private companies, adding those expenses and revenues to their own balance sheet. Taxing it would mean the federal government collects taxes on all that economic activity, and/or takes a major stake in oil companies.

While in the US this would mean a massive shift in a long history of championing free markets, there is precedent around the world – and even in US states. Norway, for instance, has grown and managed a sovereign wealth fund created through oil revenues since the 1970s, when that nation discovered oil off their coasts. Through this fund, the Norweigan government owns interests in many oil and gas companies drilling their oil fields, including a 67% stake in the largest one – Equinor ASA (formerly known as Statoil). They also collect taxes on oil revenues to the tune of 27%, with an additional ‘Special Tax’ of 51%. Returns from the fund now provide 20% of the Norweigan government’s budget, allowing citizens to enjoy free healthcare, education, and pensions.

Right in the United States, Alaska took a similar stance with their Alaska Permanent Fund – a fund that manages oil revenues from Alaskan oil fields. The fund pays out a yearly cash dividend to all Alaska residents based on oil revenues from the year. The fund has run since 1982, and is credited with bringing many people out of poverty. In 2015, each Alaskan received around $2,000 for the year’s oil sales.

The United States mining sector brought in $576 billion in 2019 – applying Norway’s 78% oil taxes to that means revenues of $449 billion. Of course, we cannot know the impact this would have on oil and gas production and exploration within the United States, but it gives us a place to start.

| $449 Billion | 15% |

|---|---|

| Heavily taxing or effectively nationalizing US mining operations | Of the way to funding a Universal Basic Income |

Future Taxes

There are several proposed taxes that could raise significant revenue for a UBI, but are so early in their development that even a rough guess at their potential impacts is difficult.

These are:

- Automation Tax

- Data Tax

- Carbon Tax

- Negative Interest Rate

Automation Tax

An automation tax would attack one of the prime reasons many people are starting to explore the concept of a universal basic income: a belief that when robots and automation take our jobs, there will be fewer employment opportunities than people. Though this fear is an age old one, some believe this time is different and a coming employment crisis will necessitate a political solution through a universal basic income.

If robots are the ones doing the productive work we used to be paid for, it would make sense to tax those robots and distribute that money to former workers. Tech luminaries such as Elon Musk and Bill Gates support the idea.

The mechanics of such a tax, however, make it very difficult to estimate. How much should a robot be paid to work? We could say ‘the wages of whoever it replaces’ – but what if it only replaces a small amount of what someone does? And how do we account for changes in wages over time? There are myriad unanswered questions here, so we’ll have to skip an estimation of the money this could raise.

Data Tax

A new ‘natural resource’ of the digital age is data. Huge corporations like Facebook and Google have grown so large on the backs of smart use of behavioral data on the internet, and now that politicians are smelling the money, the concept of a tax on data usage is in vogue.

The Guardian claims that just as oil companies pay royalties to the government for exploiting shared natural resources, tech companies should pay a tax that’s turned over to the people for use of data about citizens.

The argument, then, is that just as mining companies pay a royalty recognising the common ownership of the products they extract from the earth, a UBI would be a way of recognising the common ownership of the data that tech companies extract from us.

Tim Dunlop, The Guardian

Carbon Tax

While very politically unpopular, a carbon tax would add a tax every time energy from hydrocarbon fuels is consumed. This tax would hopefully reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pollution while raising additional revenue for the government. However, the many complexities involved in levying a tax on carbon in a highly interconnected global economy, with supply chains that can span hundreds of countries, would mean many unknown and unintended shifts in the business of burning fuel.

Negative Interest Rate

A negative interest rate is a strange concept – normally, when loaning money, the lender receives a positive interest rate from the borrower. This pays for the risk the lender takes by giving their money to the borrower, and presents a cost to the borrower to make them think twice before potentially wasting the borrowed money.

A negative interest rate flips this age-old economic wisdom on its head – borrowers are paid to take out loans, and lenders are charged for giving out their money to someone else. Negative interest rates in the financial world have existed on and off in many nations in the 21st century, and they could eventually reach your bank account and mine.

To understand this, we must remember that our bank accounts are loans we make to the bank, so that the bank can extend more loans or make more investments. A negative interest rate would mean the balance we save in our bank accounts would slowly subtract over time. Any idle cash would be subject to this negative interest rate, pushing people to invest or spend cash. The cash removed from bank accounts could in turn be used to fund a universal basic income.

However, this would likely have an immediate and drastic effect on the assets in bank accounts – as you and I would surely pull almost all our cash from the bank in order to invest it somewhere else. Unfortunately, this would have a more negative effect the poorer you are, because a larger percent of the assets of poorer peoples is kept in cash in the bank versus assets like stocks and bonds. This is antithetical to the stated goals of many proponents of a UBI, and may very well counter the intended effects completely.

Estimations are rough

It’s worth reiterating that the estimations above are all very rough estimates. The global economy is so vast and complex that our forecasts about it are almost always wrong. Unfortunately, this means we cannot say with much reliability what the effect of a new tax or a cut in spending will have on government revenues, let alone on the well-being of Americans. However, we can lay out the options as we have above, so that citizens can have a more well-informed view on policy and potential outcomes.

Universal Basic Income: Powering a New Economy?

Many supporters of a universal basic income believe it could power a new, more equitable economy with better opportunity for everyone. Detractors see an impending fall in the propensity to innovate and produce – ultimately hurting prosperity for all. Without proper funding, a universal basic income scheme could be more damaging than the worst fears of both sides of the argument, driving increased inequality under the guise of progressivism.

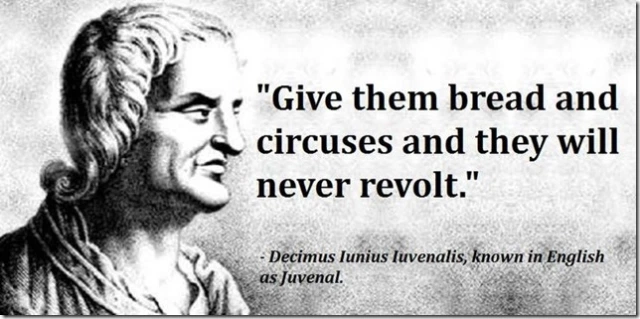

Why would a UBI without funding be problematic? For the same reason that deficit spending and the inevitable monetary debasement have caused problems for peaceful, hardworking people for millennia. The Roman Empire even tried a UBI funded by debasement of their gold coinage – now colloquially known as ‘bread and circus’ because it consisted of free bread and gladiatorial games to pacify a population suffering from rising inequality and food shortages.

A universal basic income funded through a balanced budget, however, is simply a matter of policy choice. If those who earn more are willing to subsidize those who earn less in order to create a floor, this could be a perfectly valid and possibly successful policy for a group of people or nation.

If we believe ‘money grows on trees’ – it surely won’t for much longer.

Finally, there are those who say we should just print money and give it out to everyone. But there’s a cemetery of economies full of countries who’ve tried just that: Zimbabwe, Venezuela, interwar Germany, and even the Roman empire. Economic welfare is not how much money you have, but what you can buy with it. If you continue printing money, sooner or later money will lose value.

Zilvinas Silenas, Foundation for Economic Education

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.

Credit for this piece’s featured image goes to Time Magazine.