Bankers and economists make banking seem utterly complex today, but it is actually quite simple. Banks are meant to be intermediaries between people saving money and people spending or investing it. They take money from savers in the form of deposits, and they lend money back out to help people start businesses or improve their quality of life. Fractional reserve banking allows this process to accelerate, but does add some risk.

Fractional reserve banking allows for increased investment, which often improves quality of life and development. However, it also involves the risk that depositors in the bank lose their money – depositors are compensated for this risk when the bank pays them an interest rate on their deposits.

Fractional reserve banking works by allowing banks to lend out the money they have on hand, only keeping a fraction of it in reserve. Today’s banking system, however, is in practice much different than a fractional reserve system.

How does fractional reserve banking work?

To understand how this system works, we must remember that banks originated as intermediaries between savers and spenders or entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs may need a bunch of money to build new factories, and workers may be sitting on some extra cash that they want to invest to earn a return – some interest. However, those workers don’t have the specialized knowledge necessary to evaluate businesses and other investment opportunities, nor do they have the time to develop those skills.

This is where banks come in – they specialize in making good investment decisions, and can serve as intermediaries between those who want to save money and those who need money to expand businesses. Banks make loans and earn an interest rate – say, 5% per year – and then pass on some of those earnings to the savers who provided them with the cash necessary to make those loans – say, 2% per year. The bank, for their effort in picking good investments, takes the remaining 3%. Entrepreneurs can grow their businesses, savers are richer, banks make a bit of profit.

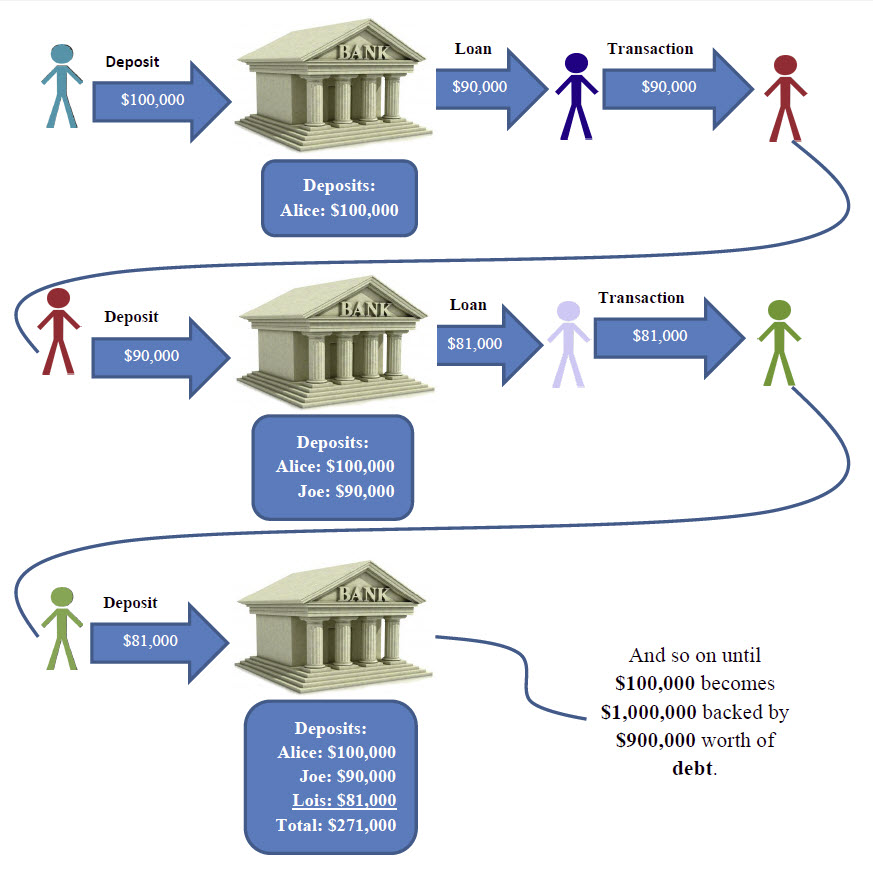

Fractional reserve banking is simply a term for how this lending process operates. When banks take a new deposit, they split the amount – some is held aside for reserves, while some is lent out to investment opportunities. Say you deposit $100 into a bank account – the bank may hold $10 in reserve, and lend out $90 to an entrepreneur to buy a factory (got a good deal). The old owner of the factory takes the $90 and puts it in a bank account as well. The bank again keeps 10% aside for reserves – $9 – and lends out $81.

There is still only $100,000 actual dollars in existence, but there is also $900,000 worth of debt that acts just like those actual dollars. Source.

This leads to a multiplication of the money in the system – hence the term ‘money multiplier’. The lower the reserves the bank keeps, the more money circulates in the economy. However, the less reserves, the more likely the bank is to suffer from a bank run, when too many depositors come to withdraw funds and the reserves run out.

If the bank lends out too much or is sloppy with their investment decisions, they risk going bust. A bank is a business, and if they do a bad job, they run out of money and fail.

What we have today in most countries operates similarly to a fractional reserve system, but lacks some of the right incentives to make banks act responsibly.

Why is the US banking system called a fractional reserve system?

Through much of the last century, the US banking system operated as a fractional reserve system with banks required to hold 10% of their deposits in reserve. However, as a result of intervention by the US central bank known as the Federal Reserve, or Fed, banks have required less and less reserves from savers to satisfy their reserve requirement.

Central Bank Money VS Commercial Bank Money

The Federal Reserve has the sole ability to create reserves for banks – this money is known as central bank money. A dollar bill in your hand is central bank money. While banks effectively increase the money supply when they make loans, they are not creating central bank money, they are creating commercial bank money.

Commercial bank money cannot be used as reserves. If banks could use commercial bank money as reserves, they could infinitely expand the money supply and make loans to anyone they wanted with reckless abandon.

Meeting Reserve Requirements

Commercial banks, like JP Morgan and Citi, care less about deposits and depositors today because they have other ways to meet their reserve requirement: selling assets to the Fed and borrowing from other banks overnight.

The first method, selling assets to the Fed, involves exchanging Treasury bills (loans to the government) with the Fed for more central bank money. The second method involves borrowing central bank money from another bank through the ‘repo market’. This little-known market is the most important market in our financial system, and the Fed also trades in it in order to set interest rates.

The Fed has time and again shown banks that it is always willing to create reserves and share them with banks by buying assets or lending in the repo market. This ensures banks always have enough reserves to satisfy the reserve requirement. In 2020, the Fed made this very clear – they would print infinite cash in order to help banks if they need it.

This sounds great, right? The Fed always ensures that a bank run cannot happen. However, this is a huge problem for the system.

The Fed Guarantee is a Big Problem

By guaranteeing that banks cannot fail, the Fed removes the incentive for banks to make smart investment decisions. Even if they make bad investment decisions and lose a bunch of money, the Fed will always step in to ensure they have enough reserves to survive, pay salaries, and even give out bonuses. This is exactly what happened with the bank bailout in 2008, and the Fed has only doubled down on their commitment to bail out banks since then.

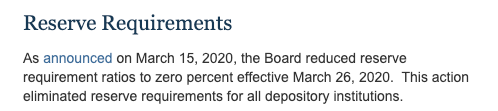

The Reserve Requirement is Gone

The Fed guaranteeing reserves all but eliminates the need for a reserve requirement, which keeps banks disciplined and smart. However, in the wake of the coronavirus-triggered 2020 Financial Crisis, the Fed actually did the unthinkable – they literally eliminated the reserve requirement. As of March 2020, US banks no longer need to keep a penny in reserve – they can lend out money infinitely.

From the official website of the Federal Reserve.

Why is fractional reserve banking bad, and what are ‘bank runs’?

A fractional reserve banking system introduces some risk for depositors, but it is not inherently bad. A bank simply adds another option for someone holding money other than keeping it in their mattress.

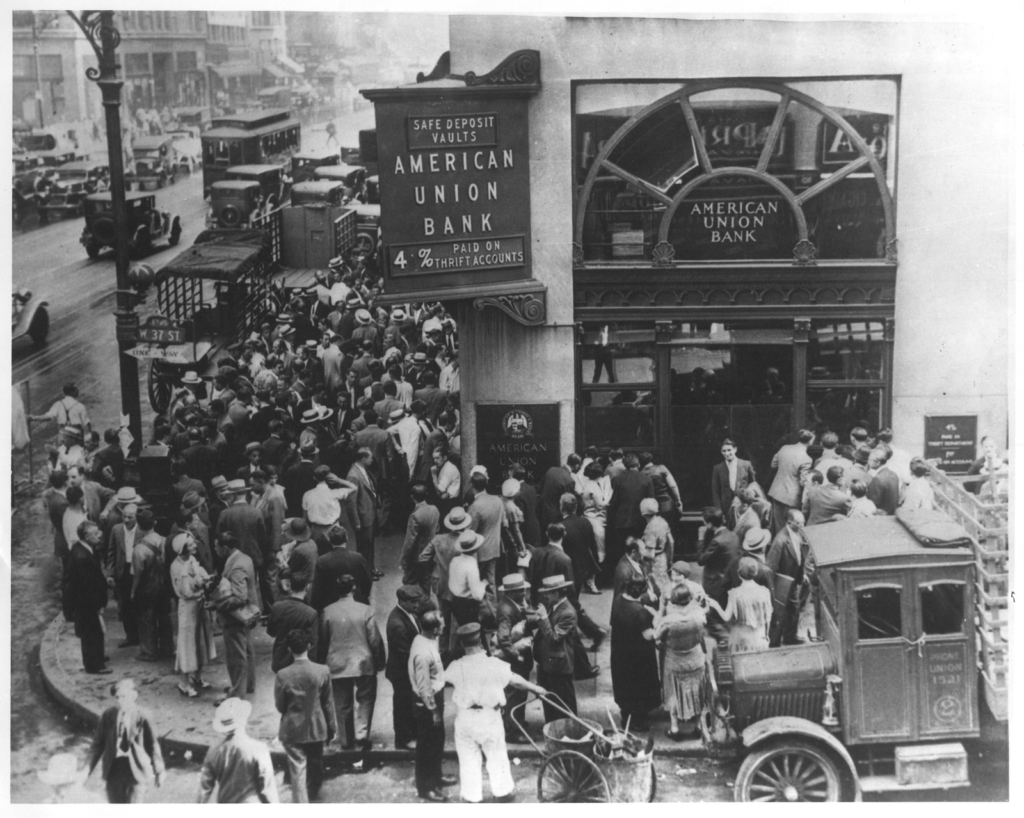

By storing money in a bank, the depositor should earn a return on their money of a few percent a year, which compensates for the small risk that the bank may fail and the money may be gone. The bank might fail because they make bad investments and do not earn enough money to pay back their depositors. When enough depositors come at once asking for their money that the bank doesn’t have enough money to pay them all, we call this a bank run.

A bank run occurring during the Great Depression. Source: Wikipedia.

Fractional reserve banking inherently involves the risk of bank runs because there will always be more money marked on the accounts than there is in the vault. Let’s say we’re in a small town, where each of the 50 citizens has deposited $1,000 in the bank. The bank then has $50,000, and they lend out 90% of it or $45,000 and keep $5,000 in reserve. If you and your neighbor need to withdraw your entire $1,000 each, you have no problems – the bank gives you both your $1,000 back, and now has $3,000 in reserves.

However, if half the town comes down to the bank to withdraw their money, the bank now needs to come up with $25,000, with only $3,000 in reserve. This is a ‘run on the bank’ and it can happen any time the bank keeps less than 100% of deposits in reserve. By definition, any fractional reserve system involves less than 100% of deposits kept in reserve, because some deposits are lent out. As a result, the risk of bank runs is inherent to any fractional reserve banking system.

Why do we use a fractional reserve banking system?

A fractional reserve banking system allows for the existence of banks as specialized investing businesses, which help drive economic growth. If banks needed to keep 100% of deposits in reserve, they would be unable to make loans. As a result, banks would not be able to pay depositors an interest rate, and entrepreneurs would find it much harder to receive funding for their business ideas and expansions.

Without a fractional reserve banking system, entrepreneurs would only have one way to receive funding – get it directly from people. The entrepreneurs would need to deal with a lot more investors (instead of one bank) and those investors would need to each understand the investment opportunity and complex risks involved. Most people would rather store their money in a bank and let them take care of the investment decisions.

A fractional reserve banking system allows banks to exist and serve a need in their communities. Banking, when done right, allows everyone to win: entrepreneurs can receive funding to build helpful businesses and savers can earn some interest just for putting their money in the bank. There does exist a risk of a bank run, or a string of bad investments causing a bank to go bankrupt. However, this risk is compensated for by the interest rate paid to depositors.

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.