Interest rates are a key part of any economy where the trade of goods and services is negotiated by people in a free market. The interest rate can be thought of as the price of money, or the result of the interaction of savers and borrowers mediated by banks

Put simply, an interest rate is the percentage of a loaned amount of money that a borrower must pay back in addition to the loaned amount. The interest rates in an economy are determined by the supply and demand for credit. The credit market is de facto controlled by central banks, like the Federal Reserve, because they are able to print their own currency and use it to extend credit to banks and governments. Banks may make further adjustments to the interest rate they offer on individual loans based on a borrower’s creditworthiness – how likely the borrower is to repay the loan.

Banks also pay you an interest rate when you deposit your money in the bank, since you are essentially lending that money to the bank. The bank can add this money to their reserves, which allows them to make more loans.

Two Key Interest Rates: APR and APY

There are two key interest rates most relevant to the daily lives of regular people:

Annual Percentage Rate (APR)

APR is the annual percentage of the total loan amount which the bank charges a borrower, including fees and discount points. An APR will usually apply to home mortgages, car loans, credit cards, and small business loans. The average annual percentage rate on a home mortgage in the US today is around 3.3%.

Annual Percentage Yield (APY)

APY is the annual percentage of the total deposited amount in a bank account that is paid to that bank account holder by the bank annually. Put simply, this is how much interest you earn on the money you deposit in the bank. The average annual yield rate on a savings account in the US today is 0.09%.

Fun Fact on APY – The Real Interest Rate is Negative

Given that dollars lose value due to inflation at a rate of around 2% a year according to the latest CPI statistics, your bank account has a negative real interest rate. A negative interest rate means you are being charged to lend your money to the bank.

The amount the bank pays you is around 0.09%, but your cash loses value at 2% per year, making your real interest rate around -1.91%. You are losing purchasing power by keeping your money at the bank, but you are losing it slightly less quickly than if you held that cash yourself.

What are today’s interest rates?

Interest rates depend on the financial product – these are the most common ones, with their current interest rates in the US shown.

| Financial Product | APR |

|---|---|

| Mortgage (30-year fixed APR) | 3.28% |

| Credit Card APR | 13.16% |

| Auto Loan (48-month) | 4.81% |

| Personal loan (24-month) | 10.57% |

| CDs (a savings product with APY) (12-month) | 0.34% |

Nerdwallet tracks interest rates on their site here.

How are interest rates determined?

To understand how interest rates are determined, let’s start by examining a common purchase many people make in their lives that involves interest rates: buying a home with a loan known as a mortgage.

Then, we’ll look at the larger market for credit that takes place at the commercial and central bank level, which affects the interest rate on a mortgage as well as all other interest rates – for business loans, auto loans, sovereign debt (the debt a government gets in to), and more.

The Market for Mortgages: How Interest Rates are Determined on Individual Loans

When someone wants to buy a house, it often costs much more than the cash they have on hand, so they go to a bank and try to get a mortgage in order to afford the house.

Getting a mortgage means the bank is extending credit to the home buyer so they can complete the purchase. In return for extending that credit immediately, the home buyer agrees to pay back the bank over a set number of years – usually 30. On top of paying back the full amount of the loan, the home buyer owes extra interest determined by the interest rate on the mortgage.

Think of interest like a rental fee – the home buyer is renting money from the bank in order to buy the house. The bank needs this rental fee to cover the risk that the borrower doesn’t repay the loan and to cover the opportunity cost to the bank of not having those funds available for other uses, like offering a loan to a different person or corporation.

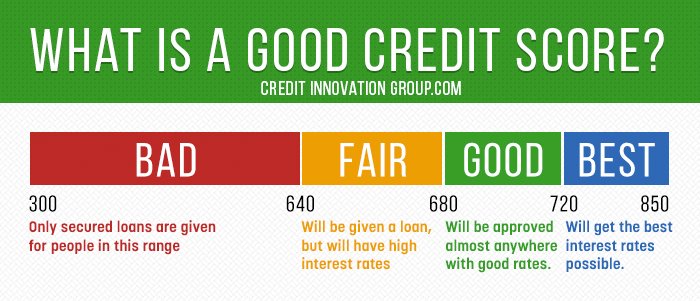

Mortgages have a fairly low interest rate compared to, say, credit card debt, because the loan is secured by the house. If the home buyer ‘defaults’ on their debt and stops paying the bank, the bank is allowed to take the house from the buyer and sell it to recoup their losses. Credit card debt, on the other hand, is unsecured – if the borrower stops paying their bill, the credit card company must call and badger the borrower until they pay back the money they owe.

Interest rates for individual loans are guided by the overall interest rate set by the market for credit (explained below), but the actual rate an individual receives also depends heavily on their creditworthiness. If a bank sees that you always repay your debts, they may be willing to offer a lower interest rate than the market rate. On the flip side, if a bank sees that someone has a bad history of not repaying debt, the bank may need a higher interest rate to compensate for the risk of lending to that person.

The Market for Credit: How Overall Interest Rates are Set

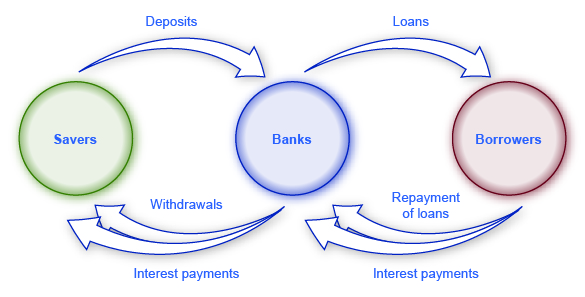

In a free market, the general interest rate for all sorts of loans from mortgages to credit cards increases and decreases based on the supply and demand for credit in the economy. Banks are simply intermediaries that match suppliers and consumers of credit, much like Uber matches drivers and riders. The suppliers of credit are savers – anyone who deposits money at the bank. The consumers of credit are borrowers – anyone that takes out a loan from the bank. Another supplier of credit is the central bank – we will bring them in later.

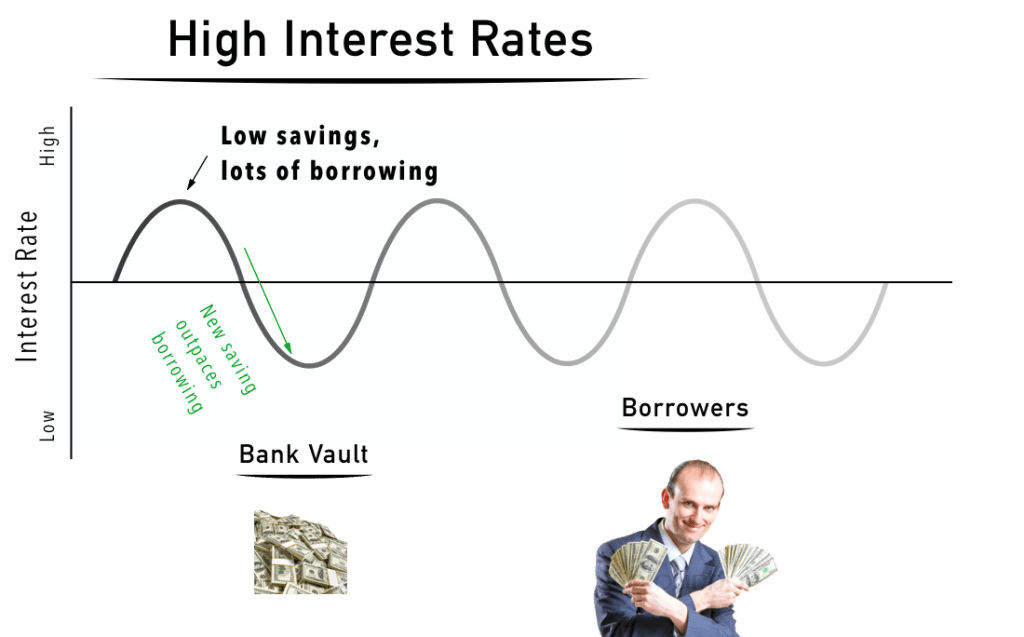

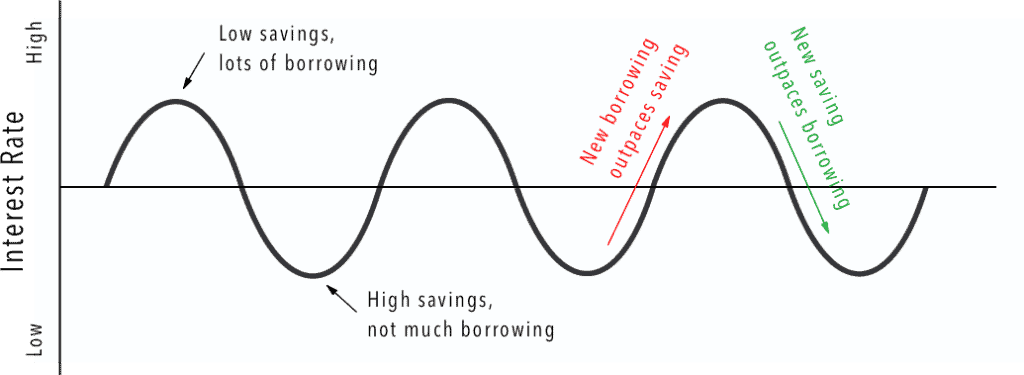

When savings are low and there is lots of borrowing, interest rates begin to rise, which incentivizes people to save more money in the bank to earn from that high interest rate (APY). High interest rates discourage further borrowing, because it’s expensive. When savings start growing faster than new borrowing, the interest rate starts to fall – the supply of credit is increasing relative to the demand for it.

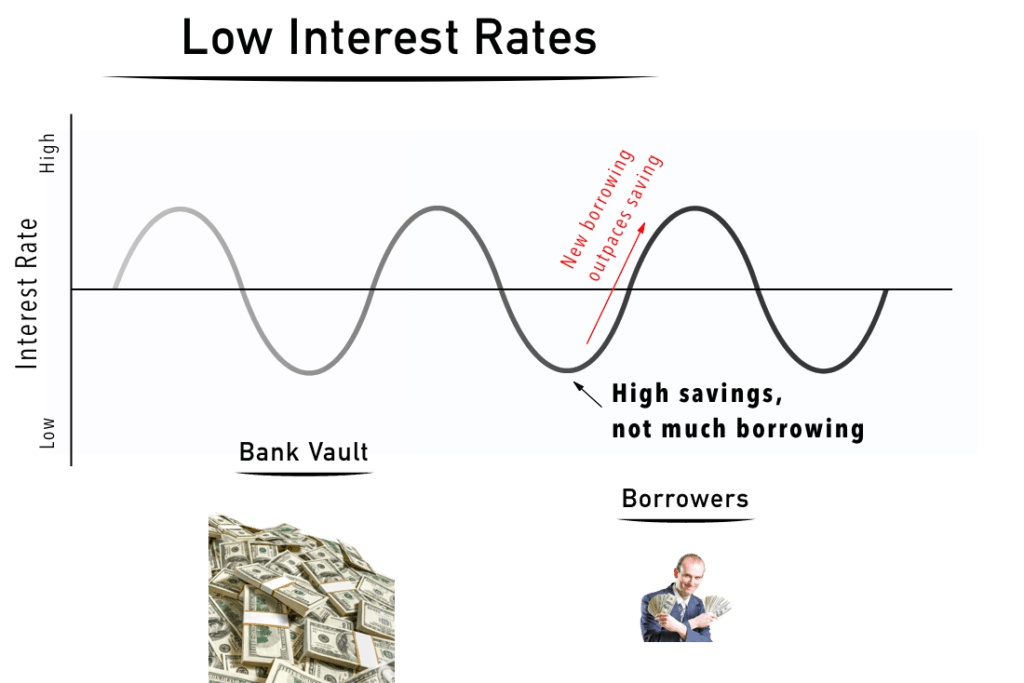

When savings are high and there is little borrowing, interest rates begin to dropdrop. Savers are now getting a very low return on their money in the bank, so they are incentivized to take their money out of the bank and invest it in riskier places for a better return. Low interest rates incentivize people and businesses to take out loans and expand operations, because it’s cheap to do so. When new borrowing starts to outpace new savings, the interest rate begins to rise – the supply of credit is decreasing relative to the demand for it. The rising interest rate tempers the speculation and greed that would take over if interest rates continued to stay low.

Generally, a turn to pessimism and uncertainty causes a rising interest rate to turn around and begin to fall. A turn to optimism and confidence cause a falling interest rate to begin to rise again, as loans increase and people begin spending or investing money.

The market naturally tamps down extremes in the interest rate and causes it to oscillate around an average. This average roughly matches the time preference of the society as a whole – meaning the level of preference for people to have things now versus later.

You may have heard that central banks set interest rates. In a sense, that is true – central banks are an incredibly powerful supplier of credit, but they do not supply money to banks by saving it – they supply it by printing it. I explain in the next section.

How do central banks like the Federal Reserve determine interest rates?

It is commonly said that central banks ‘set’ interest rates, but this process is not well explained by Investopedia, The Balance, or other financial education sites that riddle their articles with unnecessary technical finance terms.

Interest rates are not set by a free market. Central banks like the Federal Reserve are able to ‘set’ interest rates because they can do something no other player in the game can: print money. In a free market with a hard money standard – like we had under the gold standard without the Federal Reserve – it was difficult for banks to print money out of thin air. A bank that made too many loans for the amount of currency savers deposited with them (AKA the banks reserves) would eventually go bankrupt when enough borrowers defaulted on their debts and didn’t pay back the bank.

The Federal Reserve, however, can create their own fiat currency – the US dollar – out of thin air. As a result, they are not limited by reserves, and since they are connected to all the commercial banks like JP Morgan, Citi, etc – they can ensure that no bank in the system is limited by reserves. The Fed can create reserves at any time and add them to the account of any commercial bank. Here is former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke saying this, point blank.

As a result of this ability to create US dollars out of thin air, the Federal Reserve, by definition, cannot go bust. They can continue to create US dollars whenever they want. Importantly, they can also print this money and add it to the account of a commercial bank, essentially ensuring that banks like Citi and JP Morgan can never run out of cash to make loans with.

This is the meaning of “too big to fail” – these commercial banks are deemed so important to the financial system that the Fed is willing to print money and give it to these banks to hold as reserves in order to allow them to continue lending. This also keeps their stock prices high.

As a result of the Fed using their money printer, the supply of credit is always high. This artificially keeps the interest rate low, even when greed and speculation are rampant in the economy. When the interest rate spikes, the Fed just adds more cash to the system.

Here is the current President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Neel Kashkari, saying that there is no end to the Fed’s ability to pump the system full of cash:

How the Interest Rate Market Actually Works Today

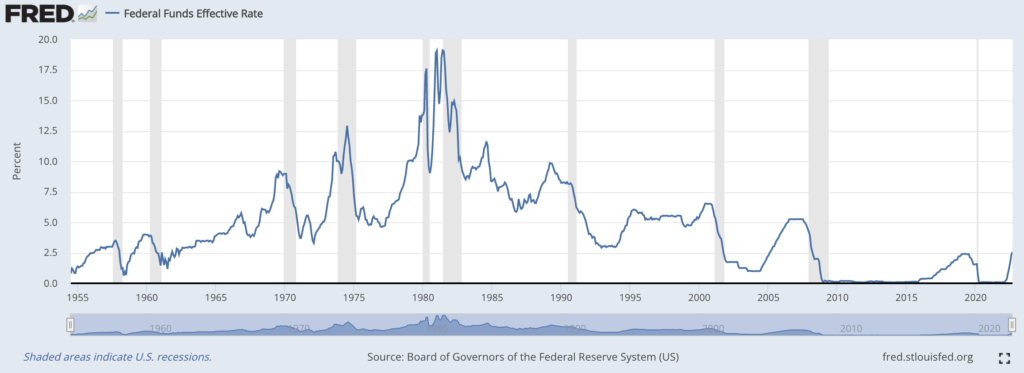

Today, commercial banks set interest rates on all the loans they offer, and their savings accounts, based on a lending rate known as the Federal Funds Rate that is targeted and ‘set’ by the Federal Reserve. This rate is the interest charged on overnight loans taken on by banks in order to have enough reserves to satisfy their reserve requirement. The Fed has set lower targets for this rate since the early 1980s, leading to a slow downtrend in all interest rates. In 2020, rates are ‘bottomed out’ at 0%, with the Fed considering negative interest rates.

The Fed sets the Federal Funds rate through a process called Open Market Operations, where the New York Fed Bank makes loans in the overnight bank loan market (also known as the ‘repo market’) using its money printer to ensure they can always make enough loans to keep the interest rate at the Fed’s target.

The Fed hopes that low rates will drive banks to lend more to businesses and consumers, who will use that money to grow their operations and buy consumer goods, powering GDP growth during crises. Let’s dig into that in the next section.

How do interest rates relate to economic growth?

Many economists say that low interest rates cause an economy to expand, but can bring inflation. On the contrary, high interest rates cause an economy to contract, but often bring deflation. While true in broad strokes, these statements have a fatal flaw – they assume that a committee of bankers can moderate interest rates better than a free market.

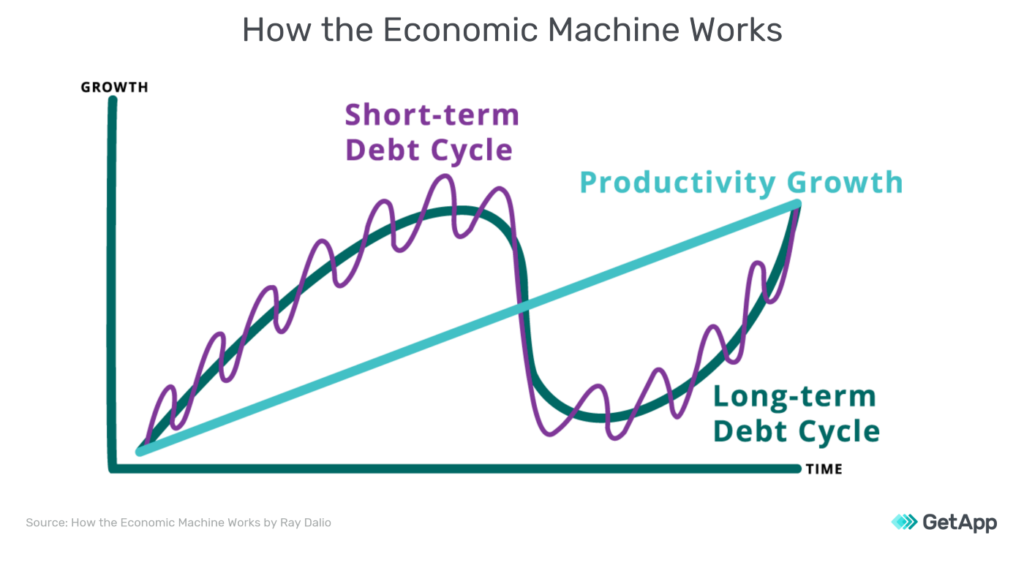

While low interest rates do incentivize more spending and investment, high interest rates are necessary to counteract the inevitable bubbles which occur in low interest rate environments. High interest rates reward saving and reign in spending, so that the cycle can repeat again with more spending to spur growth. These cycles happen around an overall trend of productivity growth, which is the only real growth that everyone should be concerned with.

Just like a muscle must stress itself and relax repeatedly to get stronger, an economy must cycle through low and high interest rates in order to grow sustainably. A muscle that works at full capacity nonstop will cramp and fail once it gives out – just as a perpetually low interest rate economy collapses harder the longer it goes on.

In a free market, cycles occur naturally around fairly constant economic growth.

Economists today are largely unconcerned about lower and lower interest rates since the 1980s because they do not believe this debt cycle is exacerbated by central banks. Traditional economic theory says that low interest rates are fine as long as we are not seeing high inflation. However, central banks measure inflation in a very narrow way, by only looking at a small set of goods and services. Unfortunately, inflation from excess supply of credit can show up in the prices for many other goods or assets in an economy.

Where inflation occurs depends on where the money from new loans goes. In our system, the commercial banks and government budget commissions make decisions on who should receive newly created money, and when the Fed keeps interest rates very low, there is a lot of new money to go around. However, we have seen low inflation in the Consumer Price Index statistics over the past decade, despite 0% interest rates for almost the entire period since 2008.

Where is the inflation?

New money increasingly goes to where commercial banks and their wealthy clients store their wealth – stock markets, bond markets, luxury real estate, even fine art. This explains why economists keep saying inflation has been so low, especially over the past 10 years, despite zero interest rates – they are not looking in the right places! The narrow and non-volatile basket of goods that the Fed watches to track ‘core inflation’ has not seen large price increases, but that does not mean prices aren’t increasing somewhere.

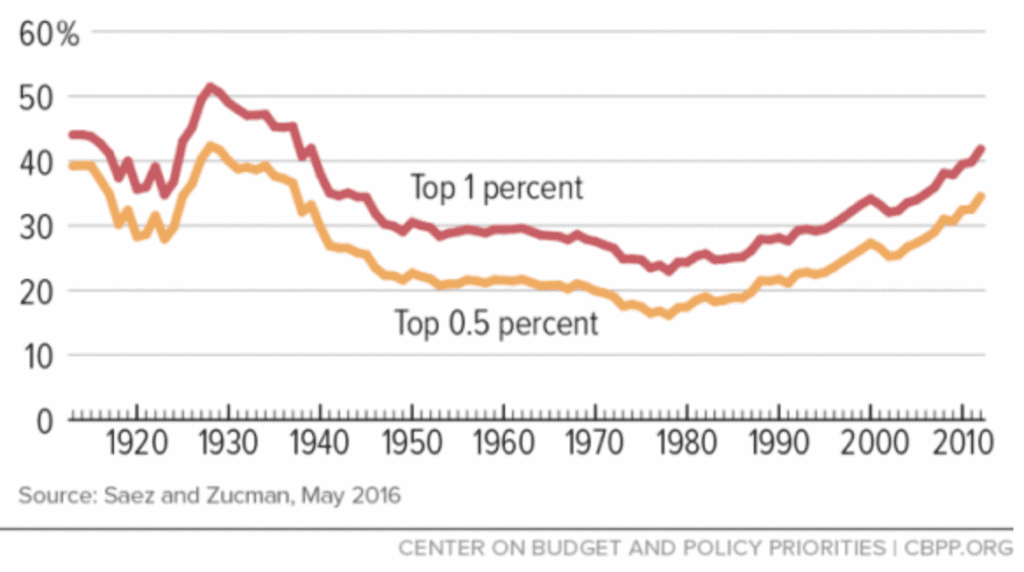

This explains the massive spike in wealth inequality we’ve seen over the past 50 years, which coincidentally began in the 1980s when the Fed kicked off a long downward trend in interest rates. Stock markets are booming (read: inflating), but the average person is not seeing wages rise.

Percentage of national wealth owned by the top 1% and 0.5%

What effect does Fed interest rate policy have on economic growth?

Overall, the Fed’s low rate policy has led to a ‘financialized’ economy, where banks, traders, and investors capture most of the profit at the expense of wage-earners and hardworking small business owners. Healthy profits for shareholders and employees come less and less from dividends and steady cash flow businesses. Instead, they come from stock price appreciation and high-growth startups that specialize in raising money rather than building products – like Juicero.

By keeping rates low for decades, the Fed makes saving unattractive and drives investment towards increasingly riskier businesses, as investors seek to find a return on their capital that they are no longer finding in savings accounts. This also makes it cheap for people with wacky, far-flung ideas to take on loans and get equity financing from investors.

These two forces reward a “get rich quick” mentality of buying assets using cheap credit, telling a good story about those assets, and selling them for a higher price to the next fund or holding company. The next company turns around and does the same thing, until there’s a contraction in credit from a crisis like the mortgage crisis in 2007 or the COVID crisis in 2020. Then, someone is left holding a failed business. If that business is deemed important enough to society by the government, they will step in to ‘bail out’ the company with the help of the money printer.

The rate cuts explain why no bank account pays any meaningful interest (APY) anymore – if banks are earning nearly zero interest on the most fundamental financial product they have (interbank overnight loans), how can they pay you for depositing?

The Federal Reserve wants to believe that they can “print their way to prosperity” but unfortunately, credit does not work this way. If credit is endlessly expanded, there comes a point where it will ‘unwind’ and come back down – unfortunately, the longer the expansion, the harder the fall.

Bottom Line

- In a free market without a central bank like the Fed, interest rates are a reflection of spending and saving behavior by businesses and individuals. If businesses and individuals are using more credit (i.e. taking out loans) than they are saving, there is upwards pressure on interest rates. If the opposite is true, there is downwards pressure on interest rates.

- In our central-bank dominated interest rate markets, committees at the Fed decide what behavior they want to incentivize. Perpetually low rates incentivize indebtedness and financialization. Artificially high rates slow down economic growth. While a free market allows for the two forces to balance naturally, the Fed believes they can guess the perfect rate.

- The Federal Reserve throughout history has always increased the amount of money in circulation by holding interest rates lower than a free market otherwise would, and rarely decreased the money in circulation by holding rates higher.

- When interest rates are held low by the Fed, your cost to get a loan is cheaper. However, you also earn less on the money you save, and must look to riskier assets like stocks to earn a return. This benefits professional money managers, while putting the average citizen at a disadvantage.

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.