Google reports the worldwide interest in the question “What is money?” increased consistently year over year from 2004 to 2019, rising sharply following the 2008 financial crisis.

And nobody seems to have a good answer to it.

However, answering this seemingly simple question will help you clarify the role of money in your life. Once you understand how money works, you’ll also see exactly why the world is going mad in the present day – and what to do about that. So let’s dive in.

When asked what money is, most people open their wallets and hold out a few bills – “this, this is money!”

But what makes these bills different than the pages of your favorite novel? Well, sure, the mint of a country printed those bills in your wallet to resist counterfeit, and everyone uses them to buy things.

However, the German Mark currency had all of these properties in the past – but businesses do not accept those bills today. In fact, German citizens burned paper Marks to heat their homes in the early 1920s. The Mark had more value as tinder than money!

So what makes money, money?

Turns out, this is not an easy question to answer.

Defining money

Money is not a physical thing like a dollar bill. Money is a social system that we use to facilitate the trading of goods and services. However, throughout history, physical monetary goods have played a key role in the social system of money, often as tokens representing value in a monetary system. This system serves three functions: 1) Medium of Exchange, 2) Unit of Account, and 3) Store of Value.

Where did these functions come from, and why are they valuable?

Here’s a table of contents for you to help you keep your place in the article.

- Functions of Money

- Money Loses a Function – The Newtonia Parable

- Money Loses a Function – The Keynesland Parable

- Is money exploiting us today?

- What is money, and why should you care?

What is a medium of exchange?

A medium of exchange is a good that is commonly exchanged for other goods. The most common explanation for how mediums of exchange emerged goes something like this:

Joel has barley and would like to buy a sheep from Fred. Fred has sheep, but he only wants chickens. Jess has chickens, but does not want barley or sheep. This is called the coincidence of wants problem: two parties must want what the other has in order to make a trade. If two people’s wants don’t coincide, they need to find other people to trade with until everyone can find a good that they want.

/153337046_10-56a27dd63df78cf77276a785.jpg)

Over time, it’s likely that certain goods, like wheat, emerged as mediums of exchange because many people wanted them. Taking wheat as an example: wheat solved the “coincidence of wants” for many trades because even if the recipient of the wheat didn’t want to use it for themselves, they knew someone else would want it. We call this property salability.

Wheat is a good example of a salable good because everyone needs to eat, and wheat makes bread. The wheat has value as an ingredient in bread and as a good that makes trading easier by solving the “coincidence of wants” problem.

Think about your desire to get more dollar bills or other currency. You can’t eat the bills to stay alive and they wouldn’t be very useful as a building material for your home. However, you know you can buy food and a house with those bills. The actual physical bills are useless to you. The bills are only valuable to you because other people will accept them for things that are useful to you. Over the long arc of history, money evolved to the point where the monetary good can have value without that good having any other ‘intrinsic’ use like food or energy. Instead, its use is to store value and easily exchange for other goods any time you desire.

What makes one good more desired and salable than another good?

Divisibility

Definition: The ability to divide the good into smaller quantities.

Bad Example: Diamonds are difficult to break into smaller pieces. For a community of thousands of people making millions of transactions per day, diamonds make a bad medium of exchange. They are too rare and indivisible to be used for many transactions.

Uniformity

Definition: The similarity of individual units of the good.

Bad Example: Cows are not uniform – some are bigger, some smaller, some sick, some healthy. On the other hand, an ounce of pure gold is uniform – one ounce is exactly like the next. This property is also commonly called fungibility.

Portability

Definition: The ease of transporting the good.

Bad Example: A cow is not very portable. Gold coins are fairly portable. Paper bills are even more portable. A ledger that simply records ownership of tokens of value (like the Rai stone system or a digital bank account) is incredibly portable since there is no physical good that needs to be carried around for purchases. There is only a system to record the ownership of tokens of value in an intangible form.

How do goods become mediums of exchange?

Goods become and stay mediums of exchange due to their universal demand, also known as their salability, which is helped by the properties above. Many different goods may act as mediums of exchange to varying degrees within an economy. Today, our global economy uses government-issued currencies, gold, and even commodities like oil as mediums of exchange.

What is a unit of account?

Things get complicated when there are many goods for sale in an economy. Even with only 5 goods, there are already 10 “exchange rates” between each of the goods which everyone in the economy has to remember: 1 pig trades for 15 chickens, 1 chicken trades for 4 gallons of milk, a dozen eggs trades for 1 gallon of milk, and so on. If the economy has 50 goods, there are 1,225 “exchange rates” between all of them!

A measuring tape for value

Think of a unit of account like a measuring tape for value. Instead of remembering the value of every good in terms of every other good, we only need to remember the value of every good in terms of one good – the unit of account. Instead of remembering 1,225 exchange rates when there are 50 goods at the market, we only need to remember 50 prices. For example, we don’t need to remember that a gallon of milk is worth 1/4 of a chicken or a dozen eggs, we can just remember that a gallon of milk is $4.

Comparing goods is easier with a unit of account

A unit of account also makes it easier to compare values and make decisions. Imagine trying to buy a pair of Nike Air Jordan shoes when one vendor is offering them for a single chicken, and the other is offering them for 50 ears of corn. The decision is far easier if one vendor charges $150, and the other charges $200 – it’s immediately apparent which pair is a better deal because they’re expressed in the same unit.

What is a store of value?

So far, we have only looked at examples of transactions that take place at a specific moment in time.

However, people make transactions over time – they save money and spend it later. For a good to function well as a monetary good it needs to hold its value over time. Money that holds value well over time gives the holder more choice over when they spend that money.

This means that the salability of a good includes its ability to hold value over time.

What makes one good a better store of value than another good?

Durability

Definition: The ability of a good to retain its form over time.

Bad Example: Strawberries make a poor store of value because they are easily damaged and rot quickly.

Difficulty to Produce

Definition: The difficulty humans have in producing more of a good.

Bad Example: Paper banknotes make a poor store of value because they can be cheaply created by banks and governments. Gold is the opposite – it is limited in supply despite high demand for it simply because it is very hard to mine out of the ground. This limited supply ensures each unit of gold holds its value over time.

How do goods become a store of value?

A good becomes a store of value if it proves to be durable and difficult to produce over time. Only time will tell if a good is truly durable and difficult to produce. This is why some forms of money exist for centuries before someone discovers a way to produce more of them, and eventually those goods are no longer used as money. This is the story of shells, Rai stones, and many other forms of money throughout history.

Gold is an example of a commodity that has served as a good store of value for thousands of years. Gold does not degrade over time, and it is still difficult to produce. For thousands of years, alchemists have attempted to synthesize gold from cheap materials with no success. Even with today’s advanced mining techniques, every year all of the world’s gold mines combined are only able to produce 2% of the total gold supply in circulation. The difficulty of gold production gives gold an extremely high “stock to flow” ratio: the stock is the existing number of units in existence, and flow is the new units created over a period of time. Very few new units of gold are created each year, even though demand for gold is usually very high.

Combining this with the divisibility, uniformity, and portability of gold, it is no wonder that gold has served humanity as a monetary good for the past 5,000 years.

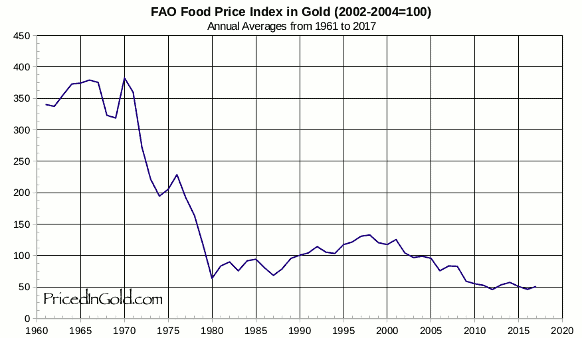

Since gold is hard to produce, we can call it hard money. As a result, it has largely held its value through millennia. The price of most goods and services in terms of gold has actually decreased over time as a result of technological innovation, which makes producing everything cheaper. Take food prices as tracked by the UN Food and Agriculture Office for example: given leaps in agricultural technology over the past 60 years, food prices have drastically decreased when priced in gold. This even holds true despite the fact that everyday people rarely use gold to purchase things.

FAO = UN Food and Agriculture Office. From Priced in Gold

A store of value allows people to save money so they can invest in starting businesses and educating themselves, raising the productivity of society. Monetary goods which store value well also encourage a longer-term outlook on life, or low time preference. An individual can work for 10 years, save a monetary good that stores value well, and have almost no fear that their savings will be wiped out by a market crash or an increase in the supply of that good.

Why are the functions of money important?

Money is a hugely important coordinating mechanism for humanity that helps everyone peacefully improve their lives together. We wrote a whole piece on the importance of money.

When a form of money loses any of its important functions as a medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value, this social fabric can tear apart. Throughout history, we often see groups of people exploiting others by taking advantage of misunderstandings about money and the importance of its functions.

Next, I will go through a bit of history on money, starting with hypotheticals to illustrate a point and then moving to real historical examples. Through these examples, we will see the detrimental effects on societies when just one of those key functions of money is lost.

Money Loses a Function: The Newtonia Alchemist

Throughout history, many goods came and went as forms of money. Unfortunately, when a form of money phases out, there is sometimes a group of people exploiting another by manipulating that money.

Let’s look at a hypothetical village called Newtonia to understand how this exploitation occurs.

Green Beads become Money

Over hundreds of years fishing in the nearby river, the villagers of Newtonia have collected green beads from the waters. The beads are small, light, durable, uniform, and rarely show up in the river. People first covet the beads for their beauty. Eventually, the villagers realize everyone else wants beads – they are highly salable. The beads soon become a medium of exchange and unit of account in the village: a chicken is 5 beads, a bag of apples 2 beads, a cow 80 beads.

The total supply of beads is fairly constant and prices don’t change much over time. The village elder is confident she can relax in her final days living off her sizable stockpile of beads.

The Alchemist creates more beads

The village alchemist wanted to be a rich man, but he didn’t like to work hard. Instead of fishing for beads in the river or selling valuable goods to other villagers, he sat in his lab. Eventually, he discovered how to easily create hundreds of beads with a bit of sand and fire.

Villagers searching in the river were lucky to find 1 bead every day. The alchemist could produce hundreds with little effort.

The Alchemist spends his beads

Being rather wicked, the alchemist did not share his bead-making method with anyone else. He created more beads for himself and started to spend them on goods at the Newtonia market. Over the following months, the alchemist bought a coup of chickens, several cows, fine silks and linens, and a massive estate. He was able to buy these goods at normal prices in the market.

The alchemist’s spending left the villagers with many beads, but few of their valuable goods.

The villagers all felt rich – they had tons of beads! However, they slowly noticed that everyone else also had tons of beads.

Prices begin to increase

The chicken farmer noticed all the goods he needed to buy at the market were increasing in price. A bunch of apples now sold for 100 beads – 50 times their price a few months ago! Even though he had thousands of beads now, he would soon run out with these prices. He wondered – could he really afford to sell his chickens for only 5 beads a piece? He had to raise his prices as well.

Put simply, as a result of the alchemist’s spending of his newly created beads, there were too many beads chasing too few goods – so prices increased. The buyers of goods were willing to spend more beads to buy the goods they needed. The sellers of goods needed to charge more to make sure they earned enough to buy the goods they needed. Since prices for all goods increased, we can say that the value of each bead decreased.

Wealth inequality grows

The village elder, who worked hard to save thousands of beads, now found herself impoverished and hungry. Meanwhile, the alchemist sat comfortably on his large swath of land with cows, chickens, and servants attending to his every whim.

The alchemist effectively stole the wealth of the village by cheaply producing beads and using them to buy valuable goods. Importantly, he bought goods before the market realized there were more beads in circulation and fewer goods, which caused prices to rise. This extra production of beads did not add any useful goods or services to the village.

Exploitation using Money: The Aggry Beads

Unfortunately, the story of the Newtonia alchemist is not entirely hypothetical. This transfer of wealth through money creation has historical and modern precedents.

For example, African tribes once used glass beads, known as “aggry beads,” as a medium of exchange. At the time, it was very difficult for the tribespeople to make glass beads, making them hard money within the tribal society. Nobody could produce beads cheaply and use them to buy expensive, valuable goods like homes, food, and clothing.

Everything changed when Europeans arrived and noticed the use of glass beads as money. At this time, Europeans could cheaply create glass in large quantities. As a result, the Europeans began to secretly import beads and use them to purchase goods, services, and slaves from Africans.

Over time, valuable goods and people were extracted from Africa, leaving the tribes with many beads and few goods. The beads lost much of their value due to the inflation of their supply by the Europeans. The result was the impoverishment of African tribes and enrichment of Europeans, as monetary historian Bezant Denier details here. Valuable goods were purchased with cheaply produced monetary goods.

Profiting off Money Production: Seignorage

This story illustrates how wealth is transferred when one group is able to cheaply produce a monetary good. The difference between the cost to produce a monetary good and the value of that monetary good is known as seignorage.

When a monetary good is much more valuable than its cost of production, people will produce more of the monetary good to capture seignorage profits. Eventually, this increased supply will cause the value of the monetary good to fall back down. This is due to the law of supply and demand: when supply increases, the price (also known as value) of the good decreases.

Money Loses its Function Part 2: The Keynesland Banker

In the story of Newtonia, the alchemist discovered a way to cheaply create more green beads out of a bit of sand. This played out in reality through trade between Europeans and Africans with the story of the aggry beads. However, these stories are a bit out of date – we are no longer trading goods for beads.

To bring us to modern day, let’s change some names in our story:

- The village of Newtonia becomes a nation called Keynesland

- The alchemist becomes the banker

- The village elder becomes the retiree

- Green beads become gold, which nobody can create more of cheaply – not even the banker.

The Banker Exchanges Paper Bills for Gold

As in reality, the banker in this story has no formula or trick to create more gold. However, the banker does safely hold the gold owned by each citizen of Keynesland. The banker gives each citizen a single receipt for each ounce of their gold he has in his vault. The receipts are redeemable at any time for the actual gold. The paper receipts, or bills, are much more convenient for making payments than carting gold to the supermarket. The citizens are happy – they have a convenient means of payment with the banker’s bills, and they know nobody can steal their wealth by counterfeiting more gold.

The citizens eventually begin to make payments entirely in paper bills, never bothering to turn in bills for gold. After all, the bills are “as good as gold” – each one represents a fixed amount of gold in the banker’s vault. A total of 1,000,000 bills circulate, each one redeemable for one ounce of gold. 1,000,000 ounces of gold sits in the banker’s vault. Each bill is fully backed by gold.

The elder who saved all her beads in the story of Newtonia is now the retiree in Keynesland, who keeps her gold with the bank and plans to comfortably live off the bills she received in return.

Let’s also add a new character to this story: the prime minister of Keynesland. The prime minister collects taxes from the citizens and uses them to pay for public services such as police and military. The prime minister also keeps the government’s gold with the banker.

The Banker Exchanges Paper Bills for Debt

The prime minister wants to make sure the nation’s gold stays safe, so he protects the bank with the police. The banker and the prime minister become close as a result, so the prime minister asks for a favor. He asks the banker to create 200,000 bills for the prime minister, on the promise that the prime minister will pay them back in 5 years. The prime minister needs the bills to fund a distant war. The citizens of Keynesland fought back against higher taxes to fund it, so he had to turn to the banker.

The banker agrees to create the bills, but on one condition: the banker takes a cut of 10,000 bills for himself. The prime minister accepts the deal the banker ‘purchases government debt.’ There are now 1,200,000 bills in circulation, backed by a combination of 1,000,000 ounces of gold and a debt contract with the government for 200,000 bills.

The prime minister spends his new bills on bombs from a ‘defense’ contractor, and the banker buys himself a plush penthouse. The defense contractor uses all the new bills from the prime minister to buy ammonium nitrate (a fertilizer used in bombs) to produce bombs. All his buying drives up the price of fertilizer for Keynesland’s wheat farmers, so they raise prices on wheat. In turn, the baker who buys wheat needs to raise the price of his bread to stay in business. It is in this way that prices around Keynesland begin to rise, just as they did in Newtonia when new beads entered circulation.

Paper Bills No Longer Represent Gold

The retiree comes across a financial newspaper that mentions the prime minister’s deal to take on debt to fund a distant war. Being wise, she knows bombs have a bad return on investment, and doubts the prime minister will ever pay back his debt. If he ‘defaults’ on his debt, that would leave 1,200,000 bills in circulation with only 1,000,000 ounces of gold to back them, devaluing her savings. She is already feeling a squeeze in her pocketbook from rising prices, so she decides to head to the local bank to turn in her bills for gold, which she knows nobody can make more of.

When the retiree arrives at the bank, she finds many others gathered around. Everyone is hoping to get in to get the gold represented by their bills. The citizens of Keynesland rightly fear that their bills are losing value – they can already feel it in the rising prices.

The door is locked, with a note from the banker:

By order of the prime minister, who fears for the stability of this banking institution, this bank will no longer support the convertibility of paper bills to gold. Thank you!

The crowd disperses, left with one choice: to hold their bills, which are now each worth less than 1 ounce of gold. Those citizens with enough financial stability to invest their bills choose to buy stocks of the bank and the defense company, which are doing well by being able to purchase things before market prices increase. Many people are unable to invest – they have to watch their wages stagnate and their savings steadily lose value.

The retiree, who was hoping to live off the bills she earned during her 40 working years, now finds herself behind the cash register at the local grocery store for 40 hours a week, wondering where everything went wrong.

The Debt is Never Paid Off

Several years pass, and the prime minister’s debt to the bank comes due. Since he spent all 200,000 bills on bombs, which don’t have a very good return on investment, he doesn’t have the bills to pay the bank back. Plus, the prime minister wants to buy more bombs for his war. The banker assures the prime minister that everything is fine. The banker will create a new debt contract for 600,000 bills, due in another 5 years. The prime minister can use 200,000 of those new 600,000 bills to pay back his original debt to the bank, keep another 300,000 to pay for more bombs, and send 100,000 to the banker to pay for his services.

This continues to happen – every time the debt is due, the banker creates more bills to pay back older debts and give the prime minister even more spending money. This cycle continues.

What happens in Keynesland?

- Those who receive new bills first see their wealth increase

- This includes the banker, prime minister, government, and those who can access opportunities to invest in the businesses who receive new bills first (financial, defense, etc).

- The prices of goods rise

- Prices don’t increase evenly – they increase wherever the new bills are entering the economy first, and have a ripple effect on markets from that point forward. In our example, the ammonium nitrate price increases first, then the wheat price, then the price of bread. And finally the wages of regular people.

- The savings and standard of living of the general population dwindles

- Those who live paycheck to paycheck and cannot invest suffer the most. Even those who are able to invest are subject to the whims of the market. Many are forced to sell their investments at low prices during market crashes just to pay for their daily necessities.

- The disparity in income and wealth between the rich and poor increases

- The wealth of the general population dwindles, while the wealth of those close to where the new bills are spent increases. A disparity results, and only widens over time.

Is money exploiting us today?

The tale of Newtonia and the real story of aggry beads in Africa feel a bit outdated. The story of Keynesland, however, feels oddly familiar. In our world, prices for goods are always rising, and we are seeing record levels of wealth inequality.

In the final section of our What is money explainer, I walk through how banking originated and the steps it took to get to today’s system, where banks and governments collaborate to control the economy and money itself.

What are banks, and where did they come from?

The emergence of banking likely occurred to facilitate agricultural trade and increase convenience. While many societies eventually converged on using gold and silver as money, these metals were heavy and dangerous to carry around in bulk. However, in many cases, they didn’t even need to be transported. Take this example:

A city needs to pay farmers in the countryside for rice, and the farmers need to pay the city’s military for protection from barbarians. In this arrangement, gold flows in both directions: out to the countryside to pay for rice, and back into the city to pay for the military. To make these transactions easier, entrepreneurs created the concept of a bank. The bank stored gold in a secure vault and issued paper banknotes. Each note stated that the holder was owed a certain amount of gold from the bank. The holder of the banknote could retrieve their gold at any time by giving the banknote back to the bank.

The customers of the bank could transact more easily with paper banknotes, but the holder of a banknote could retrieve their physical gold at any time. This made the banknotes “as good as gold.” The banks supported their operations by charging customers a fee for storing their gold, or by loaning out a portion of the gold and charging interest on it. Trade could thus happen with light paper banknotes instead of heavy bags of gold coins.

This practice of transacting using paper currency backed by monetary goods likely began in 7th century China. It eventually spread to Europe in the 1600s, and took off in the Netherlands with banks like the Amsterdam Wisselbank. The banknotes of the Wisselbank were often worth more than the gold that backed them, due to the added value of their convenience.

The rise of national ‘central banks’

Over centuries, gold started to collect in bank vaults, since people preferred the convenience of transacting with banknotes. Eventually, national banks owned by the government took over the role of holding gold from privately-owned banks started by entrepreneurs. National paper currencies backed by gold reserves at national banks replaced banknotes from private banks. All national currencies were simply receipts for gold held in the national bank’s vault. This system is commonly known as the gold standard – all currencies simply represented different weights of gold.

The gold system held up most of the time until the first World War. Governments found it difficult to raise money for this war through taxes, so they had to get creative.

When governments spend more than they earn in taxes, it’s called deficit spending. How can governments do this? Governments do it by borrowing money by selling their debt. During World War I, governments sold a type of debt called a war bond to citizens and businesses. When a citizen bought a war bond, they handed money to the government and received a piece of paper stating the government’s promise to repay the bondholder their money, plus interest, in a few years.

Central banks ‘monetize’ government debt

However, citizens and businesses were not willing to buy enough war bonds to fund WWI. Governments didn’t give up – so they asked their national ‘central banks’ to buy these bonds instead. Central banks bought the bonds, but they did not pay for them with currency backed by existing gold reserves, like citizens and banks did when buying bonds. The central banks instead gave the government new, freshly printed paper currency backed only by the bond itself. This currency was only backed by a promise that the government would repay their debts. This is known as monetizing debt.

Since war bonds and currency are only pieces of paper, they are easy and cheap to produce in abundance. What limits the production of both is trust. It only makes sense for someone to part with their hard-earned cash to buy a government bond if they believe the government will pay back its debt, plus interest. The central bank is a “buyer of last resort,” meaning they will buy their government’s bonds when nobody else will. Remember, it costs the central bank nearly nothing to buy government bonds because they just print the currency to buy them.

Imagine walking up to the most expensive car in a dealership – it costs $100,000. You think the car is nice, but you would rather spend that money on a nicer apartment – so you are only willing to pay $40,000 for the car. Now, say you have a money printer, and it only costs you $50 for the ink and paper to print $1,000,000. You would buy the car immediately, even if you had to outbid someone else and pay $150,000 for it!

The same thing happens when a central bank buys bonds (debt) from a government. The central bank can create currency so cheaply that they are willing to pay way more than others would for these bonds, and will continue to buy even when nobody else wants to.

Debt monetization causes inflation

When central banks monetize government debt, the function of money as a store of value starts to erode. The government spends the new money they got from their central bank on war goods, rations, and more. Prices for goods increase from all this newly printed currency cycling through the economy. When prices increase, it means the value of each unit of currency decreases. Everyone holding the currency now holds less value. Today, we call this slow loss of the store of value function in money inflation.

For Germany after WWI, debt monetization caused a total meltdown of the German economy, and created the conditions for fascism to rise.

As part of the ceasefire agreement that ended WWI, Germany had to pay the victors huge amounts of money. The German government badly needed money, so they sold bonds (debt) to the Reichsbank, the German central bank. This action caused the government to print so many marks (the German currency at the time) that the pace of inflation in Germany accelerated into hyperinflation in the early 1920s. The price of a loaf of bread went from 1.2 marks to 428 billion marks in just 4 years.

During and after WWI, the US, Britain, France and many other governments followed Germany by printing currency backed by government debt. This caused citizens to want to exchange their paper currency for gold, just like the retiree in the story of Keynesland. However, many governments suspended the convertibility of their currencies to gold. With this move, governments forced their citizens to hold the national paper currency and watch their savings dwindle in value. These governments could continue printing money to spend on unpopular programs that they couldn’t raise taxes to fund – like wars.

Bretton Woods: A New Monetary System

After the destruction brought on by two world wars, governments established a new global monetary system under the Bretton Woods agreement in 1944. Under this agreement, each nation’s currency converted at a fixed rate with the US dollar. The US dollar, in turn, represented gold at a rate of $35 to one troy ounce of gold*. All global currencies were therefore still simple representations of gold, through US dollars as an intermediary. Regular citizens could no longer redeem their currencies for gold from the United States. However, foreign central banks could come to the United States to trade dollars in for gold at a rate of 35 dollars to one troy ounce of gold.

However, the United States government did not always keep enough gold to back all the dollars in circulation. The US government continued to fund expanded social and military programs by selling government debt to their central bank, the Federal Reserve, which increased the supply of dollars without increasing the supply of gold backing those dollars.

*A troy ounce is a standard measure of pure gold, and is a bit more weight than a normal ounce.

The Collapse of Bretton Woods

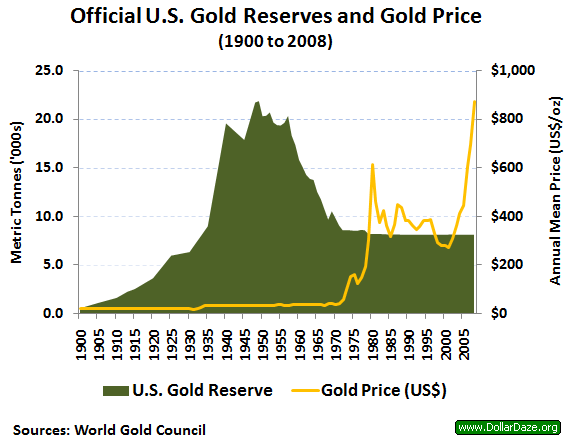

During the 1970s, rising costs from the Vietnam war and foreign governments redeeming their dollars for gold put a squeeze on the United States Treasury. Dollars increased in supply while gold held by the United States decreased.

From 1950 to the early 1970s, gold reserves held by the United States government dropped 50% from 20 metric tons to only 8 metric tons. In 1970, the nation had only $12 billion worth of gold at the official exchange rate of 35 dollars per troy ounce of gold. Over this same period of time, the total supply of US dollars went from around $32 billion to almost $70 billion.

The US government was not able to back dollars with gold at 35 dollars per troy ounce, which put the entire global monetary system at risk. By the early 1970s, a troy ounce of gold needed to be worth $200 in order to fully back all the US dollars in circulation. Said another way, the United States was trying to tell the world a single dollar was worth 1/35 of a troy ounce of gold, but in reality, a dollar was only worth 1/200 of a troy ounce. When foreign governments needed to acquire dollars for international trade and reserves, they were being ripped off. The French government realized this in the 1960s, and began selling their US dollars for gold at the official exchange rate of 35 dollars per troy ounce of gold.

Countries were starting to wake up to the US government’s scheme. The US was stealing wealth through seignorage by selling dollars for 1/35 of a troy ounce of gold when they were only worth 1/200 of a troy ounce.

The Nixon Shock ushers in ‘fiat’ money

To keep the house of cards standing, President Nixon announced in 1971 that the US government would temporarily suspend the convertibility of dollars to gold. Foreign governments could no longer claim gold with their paper dollars, and the dollar was no longer “backed” by gold. Nixon claimed this would stabilize the dollar. 50 years later, it’s clear that this only helped the dollar lose value.

Before 1971, all global currencies were tied to the US dollar through the Bretton Woods agreement. When Nixon changed the US dollar from gold-backed to debt-backed, he changed every other currency on Earth as well. He singlehandedly made the entire world economy debt-based. Currencies no longer represented gold, they represented the value of government debt.

The Gold Standard never returned

The convertibility of US dollars to gold – the gold standard – never returned. Since 1971, the entire global monetary system has run by fiat: trust in government institutions to maintain the currency system. Most currencies are backed by a combination of their government’s debt and other fiat currencies like dollars and euros. Paper currencies are no longer backed by gold, an asset that has served as hard money for over 5,000 years. Today, governments make you pay taxes in their currency and manipulate misunderstandings about money to ensure that demand for their currency remains high. This allows them to continually print more currency to spend on government projects, causing price inflation that eats away at wealth and wages.

The US government now sells government bonds (debt), known as US Treasuries, to commercial banks in exchange for US dollars. The government uses these dollars to fund its budget deficit. The commercial banks sell many of the Treasuries they buy to the US central bank, the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve pays commercial banks with freshly printed money by “using the computer to mark up the size of the account” as former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said. These commercial banks often make a profit just buying Treasuries from the government and selling them to the central bank. Buy low, sell high.

Central banks call this process of buying government debt – aka loaning money to the government – open market operations. When the central bank buys large amounts of debt at one time, they call it quantitative easing. Central banks publicly announce purchases of government debt, but very few people understand what they really mean.

The Euro, yen, and every other currency in use today functions similarly to the US dollar.

Will the US ever repay its national debt?

The strange thing about the US national debt is that the government owns the printing press needed to pay it off. As a result, when the government owes money, they just borrow more money to pay off that debt, increasing the national debt. If this sounds like a Ponzi scheme, that’s because it is – the biggest Ponzi scheme in history. Like any Ponzi scheme, it will continue as long as the people buying into the Ponzi scheme are confident they will be paid back.

If people and nations stop borrowing and using US dollars because they do not trust the US government or they see prices for goods rising (aka the dollar is becoming less valuable), demand for the dollar will decline, causing a vicious spiral. This spiral often ends up in hyperinflation, like we’ve seen in recent history with Venezuela, Argentina, Zimbabwe, and many more.

This is how the money in your bank account works. The money of every nation in the world suffers from the same problems as the beads and paper bills in the stories of Newtonia and Keynesland.

How do banks and governments steal your money?

Over the centuries, we arrived at a monetary system where banks and governments can print new currency to fund their operations and their cronies while stealing the wealth of their citizens. What happens to the world when money can be printed at will by every nation on the planet?

- The wealth of those close to the creation of new currency increases

- The government and the politically-favored class have access to newly printed money before everyone else, so they can spend it before prices rise. This effect was pointed out by economist Richard Cantillon in the mid-1700s, and is known as the Cantillon Effect.

- The prices of goods increase (known as inflation)

- All goods don’t increase in price together. Goods close to the places where new currency is produced – the financial sector and government – rise first, with a ripple effect on prices from there.

- Inflation is often represented as a change in the price for a basket of common necessities, known as the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The government has tools to manipulate this number to ensure it appears low and steady, as explained in our article on inflation.

- Financial assets often see huge inflation, but bankers don’t call it inflation – they say our economy is booming! After the US Federal Reserve quadrupled the supply of US dollars in the 6 years following the 2008 financial crisis, the banks that received these new dollars bought stocks and bonds, creating a massive bubble in the prices of these assets.

- The savings and standard of living of the population dwindle

- Wages are one of the last “prices” in an economy to adjust since they are often revisited only annually. Meanwhile, prices for that person’s daily necessities are constantly rising as new money circulates in the economy.

- Those who live paycheck to paycheck are hit the hardest – which is 70% of Americans.

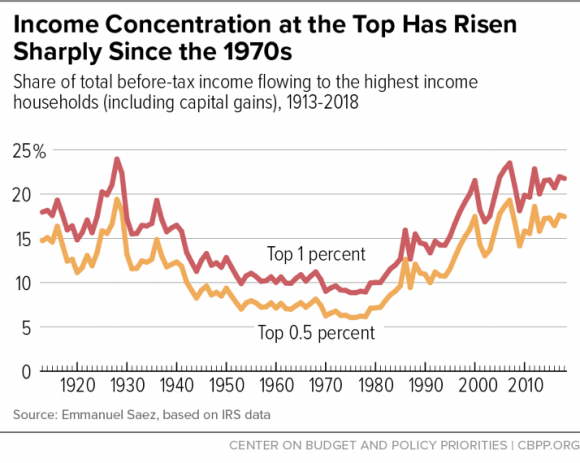

- The disparity in income between the rich and poor increases, as seen in the chart below.

Why do we continue to have the same monetary system?

If this system makes the rich richer and the poor even worse off, leading to political instability, why don’t we change it?

The biggest reason why nothing changes is likely that we are ignorant of the system itself. We all use our governments’ currency every day, but most of us do not understand how the system works and what it is doing to our societies. The education system, the media, and financial pundits constantly tell us that the monetary system is too complicated for normal people to understand. Many of us don’t bother trying.

A few other reasons why this system continues to survive:

- National currencies are often convenient

- Credit cards, online banks, and more make managing and spending national currencies seamless and easy.

- Citizens must pay taxes in their national currency

- This creates demand for that currency from all citizens, propping up its value.

- Major international markets, like oil, are denominated in dollars.

- Every nation on Earth needs oil, but since many cannot produce it locally, they have to buy it on international exchanges. Since the 1970s, almost all oil is sold for dollars on these exchanges, which creates a demand for dollars. To move away from this system, countries would need to find a new currency or commodity to trade for oil, which would require time and risk.

- No good alternatives existed

- With a global and real-time economy, our digital banking system that uses national currencies is convenient. Transacting in hard money like gold would be too cumbersome for today’s world. The digital currency named Bitcoin, introduced in 2009, is a growing alternative that offers hard money which moves at the speed of the internet.

What is money, and why should I care?

Money is a tool that makes it easier to exchange goods. Like any other good, money abides by the laws of supply and demand – an increase in demand will raise its value, and an increase in supply will lower its value. In this way, money is no different than a house or a chicken. However, the high salability of money means demand for it is always high. As a result, money must be hard to produce (and thus limited in supply) or whoever can create it will create so much of it that it will no longer serve as a store of value over time. It will soon lose its functions as a medium of exchange and unit of account as a result.

The best money in a given economy is the one which moves most freely – everyone wants it, it’s easy to transact with, and it holds its value well over time. No money is perfect at all of these, and some emphasize one function of money at the expense of others.

While history does not repeat, it does rhyme, and the rise and fall of monetary systems have distinct rhythms. The rise and fall of a monetary system often follows the general pattern we saw in the stories of the aggry beads and Keynesland: a form of money comes about to help people transact and save more efficiently, but it eventually loses its value when someone figures out how to cheaply create more of it. Over the long arc of time, however, monetary systems have improved at all three functions of money.

For example, gold has served well over time as a store of value. However, our interconnected economy could not run efficiently if we needed to exchange physical gold for goods and services. Paper and digital money is much easier to move around, but history tells us governments and bankers often use these forms of money to steal wealth through inflation.

Today’s global monetary system is very convenient, with digital payments and credit cards making it simple to spend money. This hides constant inflation that erodes the value of each unit of money and drives a widening wealth gap.

I hope this article broadened your understanding of money and its role in society. This is only the start of all there is to explore about money: saved for later are the topics of inflation, interest rates, lending, the business cycle and more.

Saving Money More Effectively

You may be wondering how to protect your savings when every form of commonly-used money and investment is suffering from supply inflation – which debases value and transfers wealth to those who can create the money or investment. It may seem like nothing on the planet qualifies as ‘hard’ money these days, but two things still do: gold, and its newer cousin Bitcoin. Both of these assets are incredibly hard to produce, and one of them moves at the speed of the internet and can be stored in your brain.

If you want to learn more about Bitcoin as a tool for protecting your savings, read here.

If you’re already prepared to buy Bitcoin, you can check out my guide to buying Bitcoin cheaply. You can start investing with just $5 or $10.

Credits

Thank you to everyone who helped draft and edit this series on money: @ck_SNARKS, @CryptoRothbard, Neil Woodfine, Emil Sandstedt, Taylor Pearson, Parker Lewis, Jason Choi, my family, and many more.

Thank you to everyone who inspired this and developed key ideas applied here: Friedrich Hayek, Carl Menger, Ludwig Von Mises, Murray Rothbard, Saifedean Ammous, Dan Held, Pierre Rochard, Stephan Livera, Michael Goldstein, and many others.

Please share!

If this article opened your eyes to how our money and financial system work, please contact me or leave a comment!

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.