Fractional reserve banking is often blamed for many of the problems inherent to an ever-expanding money supply. We hear cries that bankers are creating money to pay their bonuses, or taking too many risks with depositors’ money. However, it is not the fractional reserve, private banking system that is at fault for these problems – it’s the fact that private bank losses are socialized via central bank inflation.

Fractional reserve banking does not cause inflation in the long run, because the business cycle reins in expansions and contractions in the currency supply. It is instead central banks, with their power to create base money, that cause steady inflation over time. By stepping in to save commercial banks when they risk bankruptcy, central banks encourage more risk-taking by commercial banks – causing more crises, more bailouts, and more inflation.

To better understand these distinctions and the real reason for constant inflation over time, we will dive into the differences between monetary inflation and price inflation, base money and currency, and commercial (private) vs central banks.

By the end of the piece, you’ll have a clear understanding of how our current banking system works and why bureaucrats and governments are equally to blame as banks for the societal ills many of us associate with banking and finance. Let’s dive in.

What is fractional reserve banking?

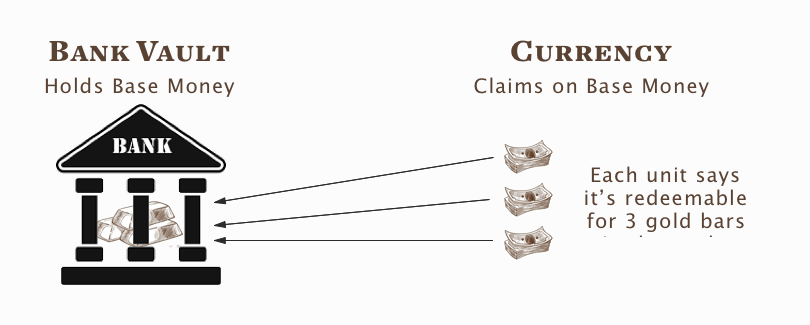

We can think of a bank as an intermediary between savers and borrowers – savers store their assets with the bank, and the bank lends out those assets (or ‘claims’ on those assets) to borrowers so they can expand businesses, make purchases, or pay other debts. To simplify a bank, it holds reserves and issues claims on those reserves. A holder of a claim is entitled to come to the bank and take reserves out of the bank.

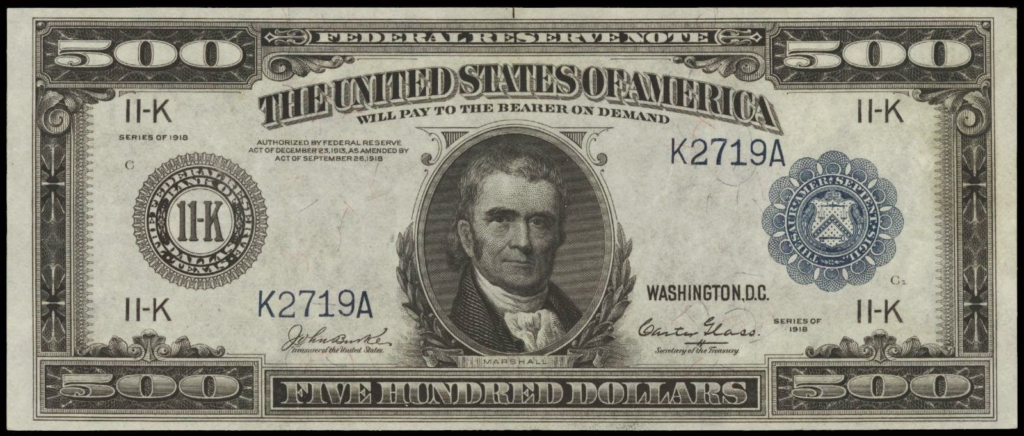

Say you hold a banknote stating that you can redeem it at any bank branch for 1 ounce of gold. This note is a ‘claim’ on the gold reserves held at the bank. These notes were similar to what we think of as ‘currency’ today – in fact, a paper US dollar at one time was simply a claim receipt for gold dollar coins held at a bank.

‘Fractional reserve’ means that the bank has issued more claims to its reserves than it has reserves to back up. The bank thus only has a ‘fraction’ of the reserves necessary to pay out all outstanding claims. This works out fine, as long as everyone doesn’t try to redeem their receipts and get their gold at the same time.

This may seem like a Ponzi scheme or a scam, but it’s similar to how many systems are engineered – think about our phone system, internet, or roads – they are not made to handle all callers, all surfers, all drivers at once. They are designed to handle a certain fraction of the total users at a given time. This reduces the cost to build and maintain the system.

Banking is no different – if bankers never created more claims (currency) than they had reserves to back, they would have a tough time making any revenue and keeping the lights on. Making loans would be difficult, as they would likely need guarantees from savers that they would not come claim their gold for some portion of time. It’s likely that the first banks actually charged savers for the service of holding and protecting their gold.

By engaging in fractional reserve banking, banks can actually pay savers a small yield in exchange for letting the bank hold their assets and lend them out, or print more claims against those assets. The bank can do this because they can make loans that earn interest, then pay savers with some portion of that interest. Banks can thus incentivize people to store assets with them, and grow their business as a result.

Of course, fractional reserve banking carries a risk for savers who deposit their money in the bank. If many claim-holders come to claim their reserves, but the bank only has a fraction of those reserves on hand, the bank can go bankrupt. I’ll discuss how this happens in the section on decreasing money supply in a fractional reserve system.

What’s the difference between monetary inflation and price inflation?

Inflation is a term we hear often in the financial press and mainstream news outlets. However, it’s unfortunately rarely defined specifically.

Price inflation is a general term for a rise in prices over time, for a set of goods or the overall ‘price level’ in an economy. References to inflation today usually refer to a very specific type of price inflation: a rise in prices for a specific basket of goods that governments believe are necessary for the average person’s survival. Importantly, this inflation is constant – taking place every year with no end or compensating deflation.

There are many complexities to how the basket of goods used to calculate inflation is chosen, weighted, and computed in many jurisdictions. I dive into the methodology used by the United States in my post on inflation – check it out if you’d like more details.

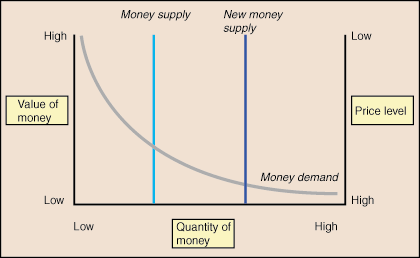

Monetary inflation refers to an increase in the supply of money. When the supply of money is increased, the value of each unit of money is pushed down, unless demand for that money also increases.

When the value of each unit of money decreases, prices rise, because a ‘price’ is just the number of monetary units it takes to purchase a good or service. Less valuable money means more of it is needed to buy the same good, service, or investment. This is how monetary inflation can cause price inflation.

In this post, we are mainly concerned about the monetary inflation caused by banks when they issue more claims than they have base money, or reserves, to back – when they operate as a fractional reserve bank. If banks are increasing the supply of circulating currency by issuing more claims than reserves, wouldn’t they cause prices to increase?

The answer is yes, but not in a sustained way. Prices may increase for a short time, but they naturally come back down, because the supply of claims (currency) created by banks must also contract. A sustained rise in all prices over time is unlikely to come from private banks issuing claims against base money reserves – this can only come from a government-allied central bank, as I’ll demonstrate.

What’s the difference between base money and currency?

So far in this post, I’ve thrown around the terms ‘money’, ‘currency’, ‘claims’, ‘gold’, and ‘reserves’ – but I’ve not done a good job clearly defining them. I wanted to lay out how they’re used first, and see if you can pick up the differences. To add a bit more clarity for the rest of your read, let me make a clear distinction between ‘base money’ and ‘currency’.

From now on, I’ll use the term ‘base money’ to refer to the reserves which a private or commercial bank stores in their vault. This has changed over time – for thousands of years, this meant gold or silver of a specific purity and measured in weight. Today, it refers to fiat currencies produced by powerful governments like the United States, Japan, China and the Eurozone.

Private or commercial banks issue ‘currency’ which represents this base money – i.e. a currency unit may entitle the holder to 2 ounces of gold held in the bank’s vault. This currency is a liability of the bank, meaning the bank is obligated to honor the promise printed on that piece of currency.

| Base Money | Currency |

| Banks hold in their vault to back up currency’s value. Cannot be produced by bank. | Claim on base money. Banks create and give out to extend loans and give savers proof of their gold held in the bank’s vault. |

| Other Names | Other Names |

| reserves | claims |

| gold | paper fiat money |

| reserve currency |

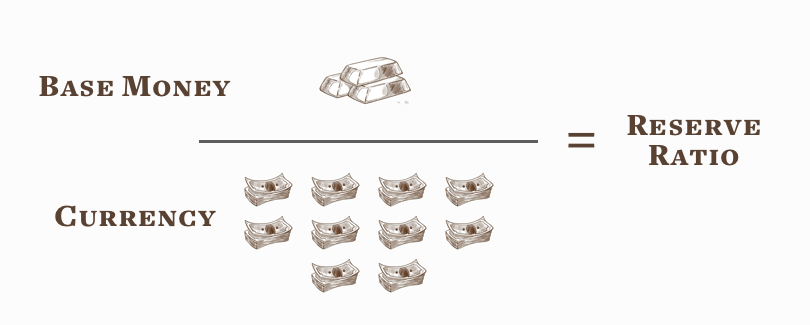

When we think about what fraction of a bank’s circulating currency are held as base money at the bank, ‘base money’ is the numerator while ‘currency’ is the denominator. If a bank prints and loans out currency that, in total, has a ‘face value’ of 10 times the base money that bank has in its vault, that bank has a reserve ratio of 10%.

Since I stated that banks print currency, you may be confused as to how our modern banks do this. We don’t see ‘JPMorgan Bucks’ or ‘HSBC notes’ in our wallets, so are our banks really producing their own currencies?

They are, however this is hidden from public view because so much of our financial system is digital today. While your bank account says it holds dollars or some other national fiat base money, that bank account is really a liability of your bank. It is bank currency. When you go to an ATM and withdraw money, you are essentially returning some of your bank currency and receiving base money from the ATM – just like going to a bank 500 years ago with a claim note and receiving a bag of gold coins.

Now that we have a better understanding of base money and currency, we can move on to showing how the currency supply changes with the business cycle.

Why do we think fractional reserve banking causes inflation?

When banks first originated, they probably charged customers to store their gold or silver with the bank – they provided protection and security. They issued claims for that gold to their customers, which – if the bank was trustworthy – would trade for goods and services at the same rate as the gold or silver commonly used in trade. A piece of paper from a reputable bank that stated the bearer could claim 5 ounces of gold would actually be worth the same as a real, physical 5 ounce gold bar when exchanged at a market.

As banks became more common and people more accustomed to trading with paper currency instead of actual base money, banks gained significant influence. By engaging in fractional reserve banking, a bank could create more currency than the base money they had in their vault.

Since the bank’s currency traded on the open market at an equal value to the base money it represented, the banker had an impact on the ‘money supply’ in the economy and thus could impact price levels. More currency circulating meant prices rose, just as if more base money – gold and silver – had been created out of thin air.

However, the rise in currency supply and resulting rise in prices would not go on forever. The more currency the bank created against its base money, the more risk it created for itself. Say the bank created 100 claims against every 1 ounce of gold they held, making the bank have a 1% reserve ratio. Only 2% of outstanding claims would need to be redeemed at once to make the bank go bankrupt. A bank that tried to operate like this would surely go bust at the first minor calamity. So, banks naturally must find a reserve ratio that allows them to survive.

The currency supply would increase to some degree as a result of the switch from a 100% reserve system to a fractional reserve one, but it would settle wherever that ‘fraction’ landed. So, say banks were comfortably able to survive through hard economic times, like droughts and pandemics, by always holding 20% of the base money needed to back up all their currency in circulation.

This would mean price levels, from a 100% reserve system, would have increased by 5 times. However, they would stay there as long as the fraction of reserves remained at 20% and the amount of base money stayed constant.

So, fractional reserve banking does cause some monetary inflation which can result in price inflation. However, this system does not cause the type of constant, never-ending inflation we think of as normal today.

How does a fractional reserve banking system reverse inflation?

Fractional reserve banking itself can actually cause price deflation, if banks and individuals use sound money like gold as their base money. Sound money is characterized by its fairly constant supply, which does not change much despite economic conditions, let alone at the whims of a few central bankers and bureaucrats.

Let’s take the example of a single bank that operates as a fractional reserve bank. This bank holds 100 ounces of gold, but through lending they issue 1,000 currency notes that each represent 1 ounce of gold – giving the bank a 10% reserve ratio. A bad storm hits, knocking out a shipping port and causing many in the city to cut back their spending and look for “safe havens” to preserve their wealth in a time when incomes from trade are dropping.

Many go to the bank to claim the gold they are owed as prescribed on the currency they hold. In this redemption process, claims are destroyed and gold is returned to owners. However, the overall supply of ‘money’ in the economy does not change, because up to now, currency holders are receiving gold at a 1-to-1 ratio. For every currency note claiming 1 ounce of gold, they are receiving 1 ounce of gold.

However, the 100 ounces of gold in the banker’s vault is soon running low, and a line forms out the door of angry customers wanting 1-to-1 redemption for their currency. This is known as a ‘run on the bank’ – and the process ends up lowering the value of the currency, possibly wiping it entirely, because all of the sudden people cannot trust that the currency will be redeemable for its face value in gold from the bank.

This drop in value for the currency against the base money (gold) it represents means an effective shrinking of the overall ‘money supply’. An easy way to think about this is to consider if the banker redeemed the first 100 1-ounce currency notes he received for 1-ounce of gold each. This would mean there were still 900 currency notes in circulation, each promising the holder 1 ounce of gold from the bank, while the bank now holds exactly 0 ounces of gold. Those 900 currency notes are now worthless, no different than a fancy piece of paper. The economy thus goes from 1,000 units of money valued at 1-ounce of gold each to 100 units of money worth 1-ounce of gold each.

This type of wind down in currency supply could also happen without a calamity, if all borrowers from the bank repay their loans. However, this would be unlikely to happen, as the bank will simply make more loans when an old loan is repaid, keeping the bank at a constant reserve ratio.

When a private bank fails like our example above, only some customers of that bank are left holding worthless paper. Often, many customers are halfway satisfied, receiving a ‘haircut’ on what they stored at the bank.

To avoid this scenario – painful both for the bank and depositors – banks must act cyclically. They can increase credit by creating more claims on their base money reserves during good times, but they must watch their risk level tightly so they can maintain solvent if and when disaster strikes. Banks in a free market must get better and better at this over time, as the ones that fail at risk management fail as businesses altogether.

Just as evolutionary processes shape flora and fauna using death and survival, the free market shapes banks using bankruptcy and profits. The risk of bankruptcy tempers the bank’s greed during good times. During hard times, the bank must reign in their excesses, recalibrate how they make loans, and improve their decision making.

So if bank currencies and credits naturally settle on a certain reserve ratio and thus money supply, why do we have constant inflation today? Why is there talk of systemic risk across the banking system? To get a clearer view, we need to understand central banking – a primary fixture in today’s fractional reserve banking system.

How does the modern fractional reserve banking system work?

The modern fractional reserve banking system includes two new players – the central bank and the government. Both play important roles in legitimizing and manipulating a new base money: fiat money.

Gold makes for an ideal base money for a banking system because it is sound – nobody has ever found a way to magically produce more gold cheaply. It must be painstakingly dug out of the ground, which makes its supply fairly constant. The total circulating supply of real gold does increase by a few percent per year, which could have a sustained effect on prices if currencies were still tied to gold, but nobody can decide to increase that inflation rate.

However, gold is not an ideal base money for a government that wants to spend more precisely because it’s hard to find. Paper currency, or digital ledger entries, are far easier to produce in large quantities. So, governments today enforce the use of their own ‘fiat money’ which looks and feels very similar to what banks have issued for centuries as claims on base money reserves, and what I call in this post simply ‘currency’. This fiat money, however, can be used by today’s banks as base money.

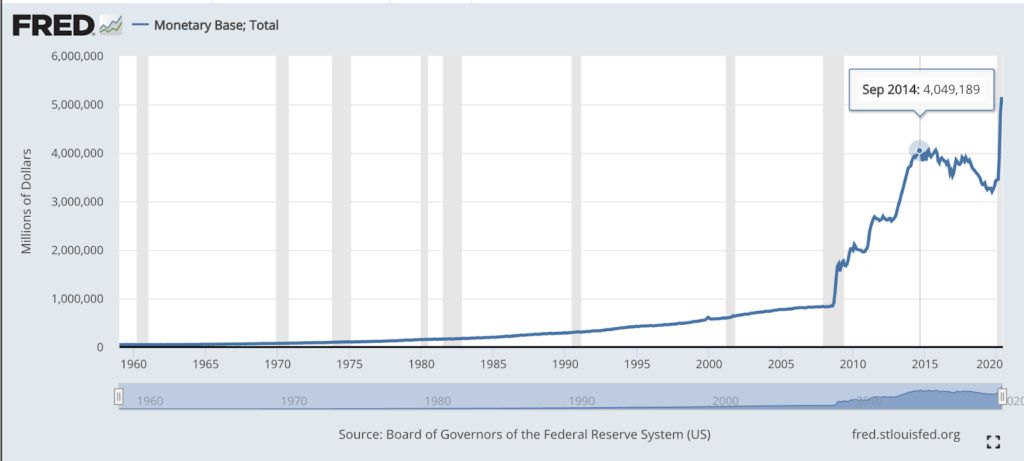

Who controls and produces this new base money? Central banks. Ostensibly in the interests of the people, central banks alter the base money supply constantly in order to induce private banks to take certain actions. In reality, they try to push private banks to act countercyclically, which is against their own best interests. Central banks lower interest rates and print more base money when the economy is crashing in an effort to drive private banks to make more loans – exactly when it is in the best interest of those banks to hunker down. When times are good, central banks raise rates and contract the base money supply to stop banks from extending loans – exactly when business opportunities may be at their best.

This interferes with the natural process of the free market – where profits and risks drive the bank to either expand or moderate their activities. This is akin to asking a group of scientists to design a bird whose body and wings were crafted over eons to achieve graceful flight. We are still trying to understand how birds fly so well – let alone successfully mimicking them with our own creations!

Besides this, central banks are also imbalanced in their actions, favoring increasing the supply of base money over decreasing it. This is the crux of the issue when talking about the reasons for constant inflation over time.

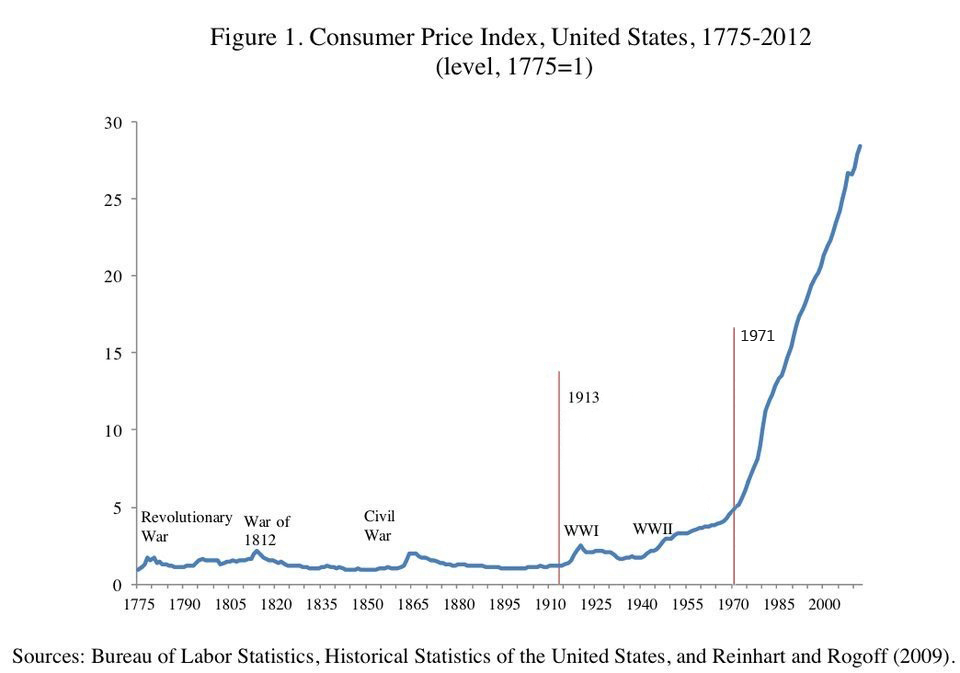

By constantly increasing the supply of base money, the central bank enables private banks to also constantly increase the supply of circulating currency. What results is constant price inflation, like we’ve seen over the past 100 years.

This has another nasty side effect – increasing risks taken by banks. Central banks always come in to ‘provide liquidity’ (aka print base money) to fill private banks up with necessary reserves during crises, when some banks might otherwise go bankrupt because of lack of reserves. Private banks have come to expect this after the many market crashes of the 1970s through to today, which means they are more inclined to take risks. Their greed is less tempered by risk, because they know the central bank will come to save them if their wild behavior gets them in trouble.

The risks thus move from the level of the private bank to the level of the entire banking, financial, and monetary system. If one bank fails, governments and central banks will come in with a program like TARP (from the US response to the 2008 crash) to subsidize the banks with taxpayer money and government debt – which must be paid off through more base money printing and its resulting price inflation.

Where does this end up? Bigger and bigger risks, deeper crashes, and greater monetary interventions from the central bank – like zero or negative interest rates, quantitative easing, and helicopter money.

A central bank that produces a world reserve currency – like the US dollar, the Euro, the Yen – can inflate the money supply for the entire world. This means the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, and Bank of Japan have the power to affect all economies, and cause risks in one banking system to potentially cause problems thousands of miles away. These central banks can even export their inflation to other countries, which they often do to developing countries.

What alternatives exist to central banking?

We are so accustomed to central banking today, which has been a fixture of the modern world for well over 100 years, that it’s hard to imagine a world without it. Our economics textbooks preach the virtues of a centrally planned money supply, and deride the ‘inflexibility’ of sound money systems. The writers of these textbooks, their parents, and their grandparents all grew up with central banks – so it’s no surprise that these beliefs are so ingrained today.

In fact, throughout most of US history there was no central bank. Prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913, price levels (as shown through the Consumer Price Index) were fairly constant. They only rose during periods of war, which often coincided with government-debt fueled overspending and paper money creation.

There are alternatives to central banking and government-decreed money: they lie in shrinking government spending and taking personal initiative to hold suitable ‘base money’ that lacks centralized bodies which control their supply.

Shrinking Government Spending

Government spending requires taxation – even if you believe in Modern Monetary Theory. Governments use violence – imprisonment, police forces, and military – to enforce that taxes are paid. However, they don’t just enforce the payment of taxes, they enforce the payment of taxes in their own base money. This creates demand for that fiat money, which props up its value, and keeps the current central banking system alive.

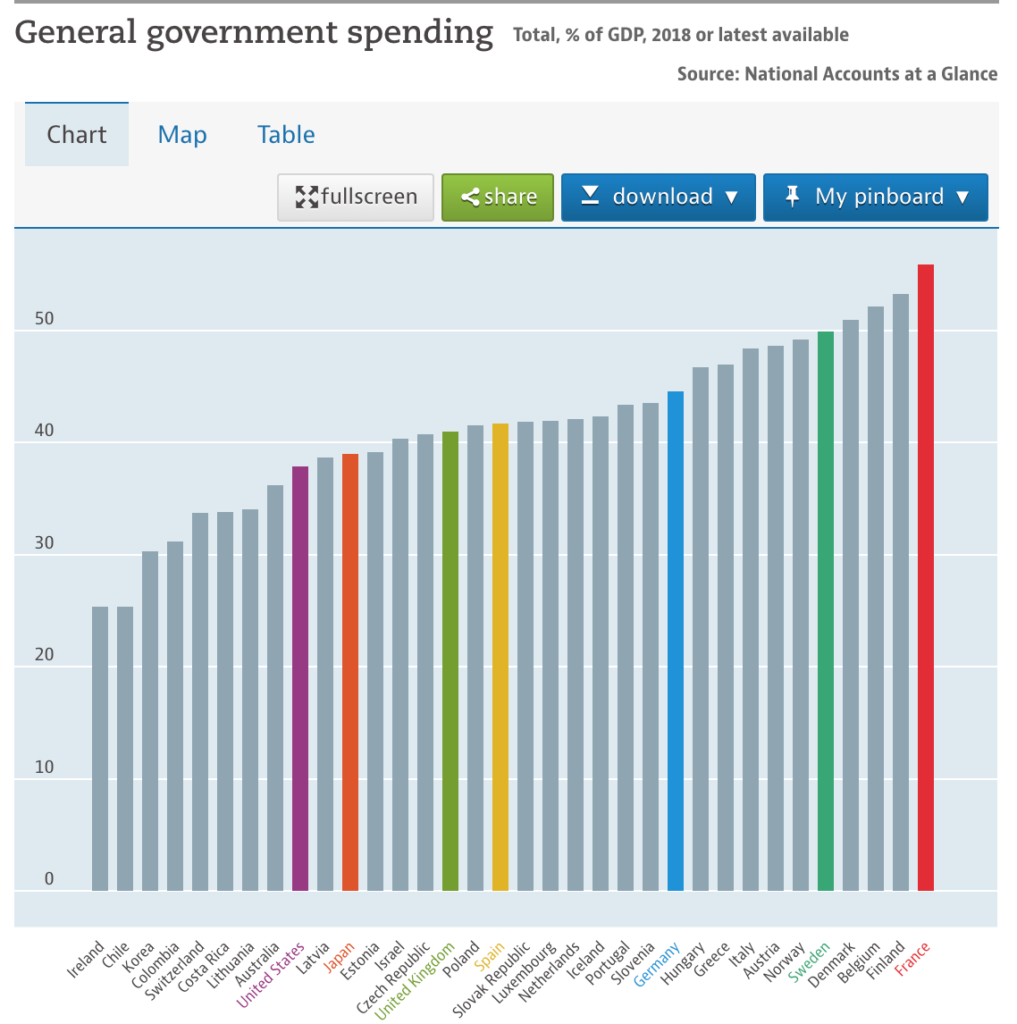

Government spending around the world today makes up a massive share of total GDP: as much as 50% of the economy in some western European countries is driven by government spending, with France leading the pack at 55.9%. Even in the United States, a bastion of free market capitalism, almost 38% of today’s GDP is made up of government spending. All this spending is financed with fiat currencies. If this spending were done by private businesses, they may choose to pay for it with different currencies or assets agreed upon by buyer and seller. Governments are such large buyers that they force their preferences on service providers – governments will only pay using their fiat currencies.

A New Base Money

Today’s fiat money makes for poor base money because it allows central planners to disrupt natural processes that moderate the excesses of private banks. Data on interest rates, base money supply, and financial crashes also show us that central banks also prefer to expand base money continuously rather than expand and contract it equally, driving private banks to increase their risk-taking.

We could return to a world where gold is used as base money – the skyrocketing gold price in the face of aggressive printing of fiat money by today’s central banks is some evidence that market participants want this to happen.

However, gold as base money is likely doomed to fail just as it did over the 19th and 20th centuries, when major developed countries like the UK, US, Germany, France and others decided to abandon the gold standard and supplant it with fiat money. Gold is simply too cumbersome – its physicality makes it a poor medium of exchange for globalized commerce. So, it inevitably ends up in increasingly centralized vaults owned by the organizations with the most guns – governments. Those governments then seize the opportunity to supplant rare base money with base money they control: fiat paper and digital currencies like the dollar, euro, and yen.

What we need is a monetary unit that can be easily transacted and stored in many places by many people. This monetary unit would be ethereal and fast, able to keep up with the speed of global commerce while also retaining the limited supply property that makes gold so stable as a base money over thousands of years.

Thankfully, cryptography enables this type of base money – a unit that banks could use as reserves to make loans against, but which individuals could easily hold and store themselves if necessary.

Individuals will need to choose to trade their fiat money for this new base money in order to buck the power of central banking and the fiat system. Some may choose to purchase it to speculate, while others may hold it to save their wealth in the face of sustained and increasing inflation – the slow death of value in fiat money.

A return to fractional reserve banking with no inflation?

If free individuals choose a new base money, the government-sponsored fiat money system would begin to dismantle. Government spending would necessarily drop as well, as taxation would continue to function less effectively over time.

Free banks could adopt this new base money instead of fiat money as reserves, and return to a banking system where natural free market forces reign in bank greed and excessive lending, putting a damper on speculation and market bubbles.

In short, fractional reserve banking does not cause inflation. It is central banking and governments – and their forcing of private banks and whole economies to use paper fiat money as base money – that drives constant inflation.

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.