Understanding and monitoring inflation is a tricky thing for the government agencies tasked with ‘officially’ recording the numbers, let alone for households just trying to buy their daily necessities. Economists have noticed one ‘fallacy’ about inflation slipping through the cracks, but in fact, it’s really a useful rule of thumb for everyday people.

The inflation fallacy means believing that a rise in prices means an equal loss in purchasing power. Many economists argue that every purchase is another person’s income, so this cannot be true. However, it is a useful rule of thumb for anyone who lives off a wage.

This fallacy persists because it hides an ugly truth about how inflation works. Looking at an economy from an overall view, we see that every dollar spent is someone else’s income. However, this does not do a good job of explaining how inflation actually works in the real world. The structure of inflation today, unfortunately, greatly affects winners and losers in society.

Understanding the Inflation Fallacy – Truths and Misconceptions

The inflation fallacy is rooted in the idea that accounts must balance in an economy. When you spend money, that money ends up in the hands of someone else. So when prices rise (aka price inflation), your increased spending becomes someone else’s increased income. In this way, everything balances out.

However, this view of inflation is zoomed out from the lives of everyday people. By taking ‘the average’ of all economic activity, we account for nobody’s actual lived experience of inflation. To better understand why the inflation fallacy persists, we should not blame people’s ignorance of economics (as economics PhDs love to do!), and instead think about why people feel the fallacy is true.

People believe that rising prices are hurting their purchasing power because, well, they are. To understand why, we need to look at the ‘balance sheet’ of a household, which consists of:

- Income: The money regularly coming in. For many people, this is a wage or a salary.

- Expenses: The money regularly coming out for living expenses and liabilities.

- Assets: The saved money and investments someone has, some of which may provide income (like rental properties)

- Liabilities: Obligations to pay money in the future – like a mortgage or loan.

If the “price” of their income or assets increases as a result of inflation – like getting a raise or seeing a stock they hold increase in price – they are better off. If the price of their expenses or liabilities increases as a result of inflation – like grocery prices or their mortgage rate increasing – they are worse off.

For most people in the developed world, their income is solely from a wage or salary. This wage or salary is what economists call sticky – it usually changes at most annually, if that. Their other expenses, like groceries, are subject to price increases at any time.

When income increases only once a year due to inflation, but expenses increase relentlessly, people do suffer from decreased purchasing power – just as the inflation ‘fallacy’ suggests. Any savings they hold in cash also dwindle in value.

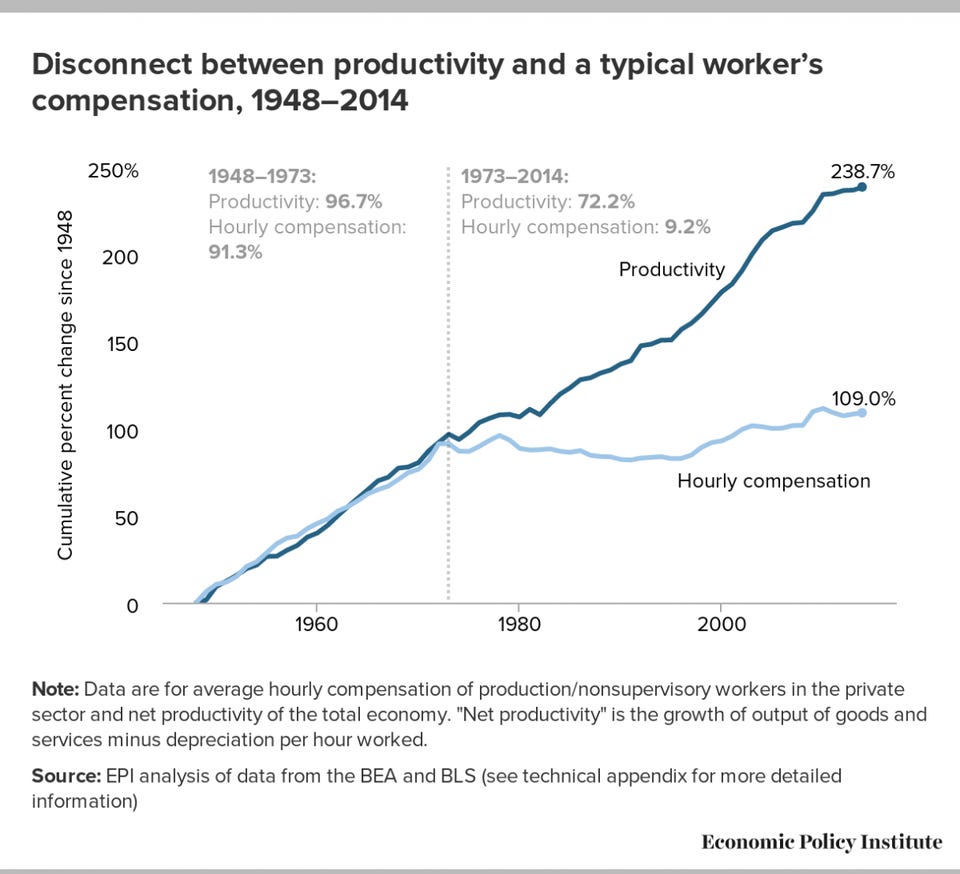

Unfortunately, this isn’t just a flippant example. Economic data backs up the fact that wages have been stagnant since the 1970s, while productivity has increased.

But every dollar spent is another person’s income – so where has that money gone?

Inflation Benefits Someone – Introducing the Cantillon Effect

The inflation ‘fallacy’ is a fallacy because everyone’s spending is another person’s income. However, most wage and salary earners are seeing their income and savings reduced in purchasing power by inflation. So where is that money going?

This question brings us to the Cantillon Effect, the name for how inflation impacts people’s wealth. The Cantillon Effect describes how those who are close to the creation of new money are able to benefit from that money more than others, because they are able to spend that money before inflation happens.

Think about it this way: If I printed $10 trillion in cash and gave it to you, you could go out and buy a mansion, a nice car, and more at the same prices as they were selling for yesterday. However, once you start spending a lot of that cash, prices will begin to rise as people start to realize there’s a ton of new money in the system – this is inflation happening.

The slower someone is to raise the prices of their goods or services as a result of all this new money circulating, the worse off they are. These people are selling goods and services at low pre-inflation prices, but paying for other goods at high post-inflation prices.

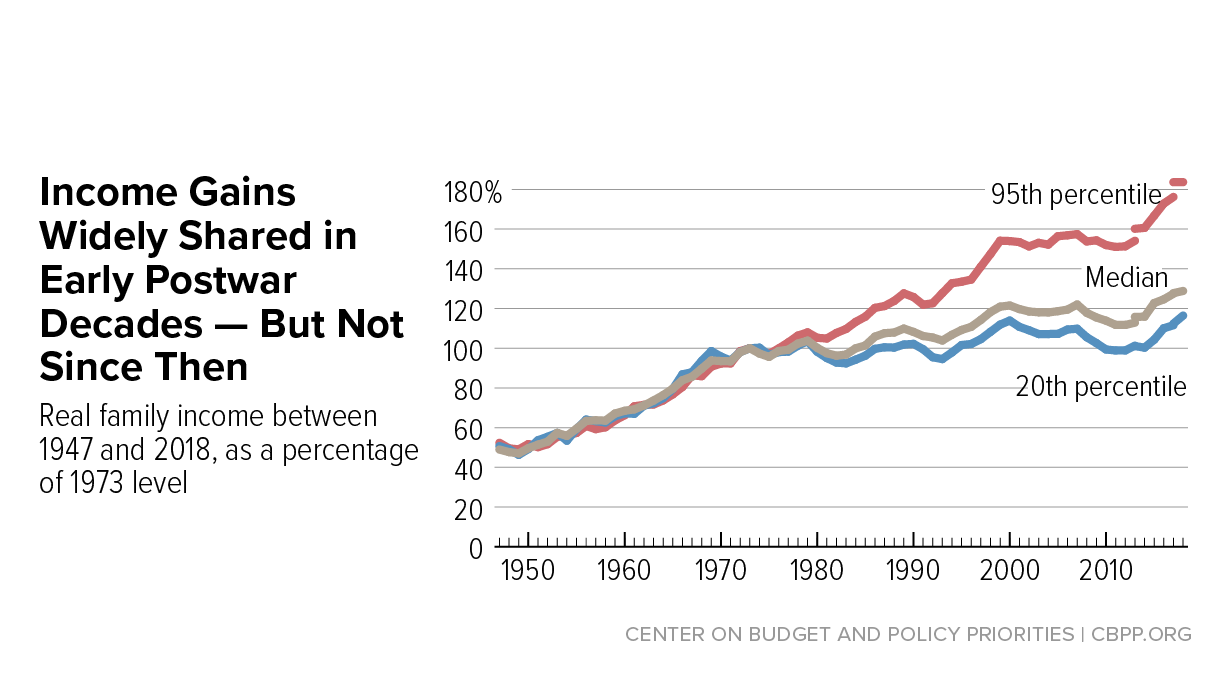

This is the Cantillon effect – the closer you are to the source of money’s creation, the better off you are. Those who earn a wage or salary are often the last to see the price of the service they sell (their time, energy, and ideas) increase, so they are hurt by this system. This was poignantly illustrated in 2020 when the NASDAQ had its best week in 100 years, while unemployment also reached levels not seen since the Great Depression.

Today, banks and the government are creators of money, so the politically well-connected class of financiers and contractors benefit the most from the Cantillon Effect.

What’s the result? Rising wealth inequality.

Protecting Yourself from Inflation

Inflation reduces savings and the value of your wage or salary, so to protect yourself, you’ll need to find assets that are resistant to inflation. Not so long ago, banks used to actually pay you an interest rate on your deposits that exceeded inflation. However, we are not so lucky today – banks pay us just above 0% in interest, so we actually lose value by putting our money in a bank.

We can put our savings into riskier assets, like stocks and bonds, but these regularly suffer from swift and strong downturns. When those downturns are combined with lost jobs due to a recession or depression, you may be forced to sell just to survive. Putting money in government treasuries, like TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) is a good bet, but you may be supporting a government you don’t agree with by doing so.

The best assets for protecting yourself against inflation over a few years or more are gold and Bitcoin. Both have a very strictly limited supply, so it is hard for people to create and sell a bunch more of them to drive the price back down if their price increases. Gold has fairly low volatility in purchasing power given its 5,000 year history of use as money. Bitcoin, being only 10 years old, is wildly volatile – but grows by leaps and bounds in purchasing power every few years. In 2010, just 10 years ago, someone purchased two pizzas for 10,000 bitcoins. Today, that same amount of bitcoins is worth 10s of millions of dollars.

Related Questions

What is ‘shoe leather cost’ in economics?

‘Shoe leather cost’ is a term for the cost of the time and energy it takes to research, understand, and invest in other assets in order to protect your wealth from inflation. Most people with a full time job have little time and energy left to do this, and instead pay fund advisors and ‘experts’ to invest their hard-earned money. These costs and fees can also be thought of as ‘shoe leather cost’.

The term comes from the idea that during periods of high inflation, people would keep their money in a bank account that pays them interest that’s equal to inflation, and only carry a bit of cash with them at a time. The many trips to the bank to withdraw more money wore away at their shoe leather, so they would have to replace their shoes more often. The cost of that worn shoe leather is the extra cost inflation adds, even if the interest rate paid by their bank protected their wealth from inflation. Today, this cost is paid in fees to financial advisors and time spent learning about stocks and other assets – because bank accounts pay 0% interest.

What does ‘money neutrality’ mean?

Money neutrality is an economic term for the idea that any newly created money circulates evenly throughout the economy in the long run. While that might be true at the aggregate level of an economy, it tells us nothing about the individual lived experience of people in that economy. The Cantillon Effect tells us much more about reality than the theory of ‘money neutrality’.

What is the difference between real value and nominal value?

Nominal value describes an item’s price in terms of a monetary unit, like the dollar. Real value instead describes an item’s price in terms of goods and services. While nominal values are more commonly used and easier to understand, real values are adjusted for inflation.

For example, if your stock portfolio increases from $1,000 to $2,000, you may think you are wealthier now – the nominal value of your portfolio just doubled. However, if your expenses (rent, food, medical care, etc) collectively rose in price 5x over the same period, you are actually poorer in real terms. The real value of your stock portfolio has actually decreased, because it can buy you less goods and services.

In the end, real value and prices are the only thing we care about, but nominal value is what’s talked about on the news and put on price tags.

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.