Banks are misunderstood and complex entities. At their core, they are simple financial intermediaries – matching savers with borrowers – but over time they’ve branched out into new business lines.

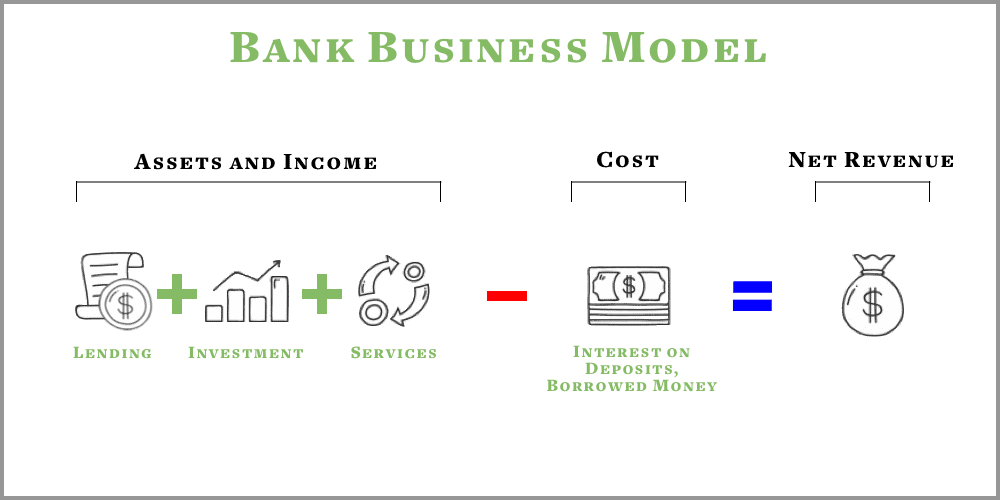

Today, banks primarily earn money in three ways: lending, investment, and services. Within each of these categories, there are numerous major businesses such as auto loans, home loans, credit cards, small business loans, bond or equities trading, wealth management, corporate bond underwriting, mergers and acquisition advising, and restructuring.

In this article, I will dive into how banks earn money, their role in the economy and the primary business models they pursue.

- What is a Bank?

- 12 Ways Banks Make Money

- 3 Types of Funding for Banks

- 3 Primary Banking Business Models

What is a Bank?

A bank takes currency from depositors and lends or invests that currency to earn a return. Depositors are lending their currency to the bank, so the bank has to pay them some interest for letting them borrow that currency. The bank earns an interest rate when it lends currency out to borrowers to buy homes and cars or to start businesses. The bank also charges various fees and earns revenue off services, which add to its income. The difference between the revenue from lending and the cost of borrowing for a bank make up the bank’s net revenue.

This is an important service in any modern economy because it allows savers to grow their savings just by lending their money to a bank, and it allows businesses and individuals to gain access to money they need to improve their quality of life or expand their business.

Today, we operate in a fractional reserve banking system where banks are required to keep some percentage of the total deposits lent to them on hand, in case depositors like us want to withdraw our money from the bank. The rest can be lent out to earn interest.

This means the cash in your bank account is actually just a credit to you, and liability of your bank. Those numbers on your bank statement do not mean the bank has your cash in a vault – it just means the bank is promising to find and deliver you that cash if you try to withdraw it. However, if too many people want to withdraw at once, we will experience a ‘run on the bank’ where the bank does not have enough currency to return to everyone their money.

We will get into the fractional reserve system and the role of funding sources later, but first, let’s cover 12 ways banks make money.

12 Ways Banks Make Money

Interest Income from Lending

Most banks earn the majority of their income from lending money to individuals and businesses. According to a study by Ernst & Young of 3,691 banks mainly in the E.U., 59% of bank income comes from interest on loans (Page 10, Table 2). A paper by the Bank of International Settlements studying 222 banks from 34 countries shows this is likely to be correct, as 57% of bank assets are in loans (Page 5, Table 1).

Smaller banks tend to rely more on interest income, with 67% of their income coming from loans. Banks that source most of their income from interest tend to get their funding from retail deposits – you and I depositing our paychecks into the bank.

Retail Loans – Auto and Home

Retail loans are an important part of life for most middle-class people and a big business line for banks, especially in the United States. Homes and cars are large purchases that many people would like to make before saving the total amount of money necessary to buy these goods with cash.

To satisfy this need, banks take a look at a borrower’s credit score – a judge of that person’s history repaying debts – and their income. If the bank believes they’ll be able to earn a good return from the borrower, they will offer a mortgage so that the home buyer can move in immediately.

In return, the home buyer signs an obligation to pay off their debt steadily over a period – usually 30 years. The home buyer pays off the total amount lent, known as the principal, as well as interest on top at a set (or variable) rate, like 4% of the principal annually.

This market was the center of the 2007 financial crisis, since banks used clever financial engineering to package up bad mortgages in such a way that they looked like good assets, then resold those mortgage packages to other financial players like pension funds. In the end, this encouraged banks to give anyone and everyone a mortgage, even if those people clearly could not repay that mortgage.

The banks ‘traded away’ their risk because they sold the mortgage to ‘greater fools’ at a healthy profit. When the borrowers could no longer repay, those holding the mortgages (who were entitled to regular payments) were left with an asset that suddenly had no value. The banks still had their profit from selling these mortgage packages.

Credit Cards

Credit cards are a key part of our global and digital economy, with over 60% of individuals in most developed countries – like the US, Canada, Japan, Korea, and Switzerland – having at least 1 credit card. In the US, the average adult has more than 2 credit cards, and importantly for banks, the average credit card debt per person in 2019 was $6,194 according to an Experian State of Credit report.

A credit card is essentially a short term ‘unsecured’ loan from the bank that you can use to purchase many types of goods and services. They come with limits on the amount you can spend per month, but there is no asset the bank can take back if you decide not to pay your credit card bill on time. This is in contrast to a home or auto loan, where the bank can take your house or car if you fail to pay your bills on time – this is known as a ‘secured’ loan.

The unsecured nature of a credit card means the bank takes on more risk by letting you use one. As a result, banks usually charge high interest rates for credit card debt if you fail to pay your bill on time, usually around 15% – 20% annual interest on any unpaid balance.

Business Loans

Business loans come in many varieties, but the two main types are small business loans and commercial financing. Small business loans often have set terms and a fairly simple process for applying. They are similar to credit cards or home loans, in that they can be structured as a ‘line of credit’ like a credit card that can be spent and paid off continuously, or they can be structured as lump sum loans paid off over time.

However, instead of providing information on personal finances, applying for a business loan requires proving to the bank that a business is healthy and earning money by showing financial statements and a business balance sheet. The health of the business also affects the interest rate on the loan and the total loan or credit line amount. The loan terms may also require some collateral to be ‘posted’ in order to secure the loan – this could be a piece of real estate or equipment owned by the business. In case the business can’t repay the loan, the bank would be able to sell this piece of collateral.

Commercial or corporate financing deals with larger businesses that may want to finance expansion, acquire other companies, or purchase inventory. These loans are often custom made for each business and financing scenario, but come with higher fees and larger interest payments due to the loan sizes. This allows the bank to spend more time and resources on crafting these deals.

Interbank Lending

Interbank lending is a special type of lending activity that is uniquely important in our current monetary system. Interbank lending involves banks loaning reserves to each other, usually to satisfy their regulatory region’s ‘reserve requirement’. The term for these loans is often literally overnight, and the loans are usually secured with very high quality, low risk collateral like government debt securities.

We will dive more into the role of interbank lending below when discussing the role of funding in bank operations.

Non-Interest Income from Investment

This type of bank income is fairly simple – it is the income from buying low and selling high, or selling high and buying low. When this is done over a long time period, we call it investment. When it’s done over a short time period, we call it trading.

Banks that take on trading and investment activities tend to be larger banks that borrow heavily from other banks and financial institutions. The Bank of International Settlements calls these banks ‘Trading banks’ and notes a start differentiation between their funding sources, with almost 20% of their funds coming from interbank lending (Page 5, Table 1). They have a smaller share of loans as a percent of their total assets, at only 25% versus over 60% for banks that engage primarily in lending activity.

Regulation also plays a key role here. In the United States, the Glass-Steagall Act, which was in effect from 1933 until its repeal by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act in 1999, prevented banks with federally-insured deposits from investment and trading activities. The Federal Depository Insurance Corporation, also founded in 1933, insures many types of bank accounts up to a certain amount – currently $250,000. This means if a bank fails, depositors like you and I will get our money back thanks to the FDIC – even if they have to print fresh currency for us.

After the 2008 financial crisis revealed that banks undertook highly risky activities with federally-insured deposits, therefore putting the US government at risk of bailing out banks for their mistakes through the FDIC’s insurance, the Dodd-Frank Act was passed in 2011. The Volcker Rule provision in this Act brought back some of the divisions between depository institutions and investment and trading activities, while still allowing some crossover.

The EU attempted to pass similar legislation but did not succeed. There are no limits on the use of depository funds in investment and trading activities in the EU.

Equity Investments

Investing carries higher risk than most lending activity because the structure of modern corporations means equity holders (investors) are the first to have their value wiped out in the event the business fails, before bondholders (lenders).

Nevertheless, this can be a very lucrative business for banks, as they can use leverage and good sales tactics to quickly make a large return on investment. In this type of deal, a bank or ‘private equity’ (PE) firm raises money from investors or other banks in order to purchase a company or other large, complex asset like a piece of real estate. The bank or PE firm then improves the asset and resells it for a higher price. After paying back investors, there is often a very sizable profit for the firm thanks to the leverage used by the bank to buy the asset.

Under the Volcker Rule, US banks are allowed to invest up to 3% of their Tier 1 capital in hedge funds and private equity funds that specialize in these investments.

Forex, Commodity, Equity, and Bond Trading

Trading is simply the short-term version of investment, and usually involves more liquid investments that are heavily transacted in – like commodities, currencies, bonds, and stocks (also known as ‘equities’). Trading represents around 10% – 15% of the overall revenue of a bank, but differs widely depending on the regulatory environment the bank operates in.

Under the Volcker Rule in the US, banks are allowed to trade government bonds like Treasuries and municipal bonds freely, but are subject to limitations on trading of assets that are not government-backed. This allows the US government to continue selling Treasuries to the US central bank, other financial institutions, and foreign governments using banks as ‘primary dealers’.

Non-Interest Income from Fees and Services

Aside from income earned through lending and investment, banks make a big chunk of their revenue off fees and services. This type of income represents 26% of income for all banks sampled in the aforementioned Bank of International Settlements study, and 44% of income for banks categorized as ‘trading banks’. This is where niche investment banks and arms of larger banks make their profits, as these business lines do not require deposit funding but rather focus on offering advice, financial smarts, and the right connections to clients so they can access capital and do the most with it.

There are two main areas banks earn fees: retail banking and commercial banking. Retail banking fees are being eaten away by digital innovation, while relationship-centric and regulation-focused services like fundraising, restructuring, and acquisitions are booming business segments.

Transaction Fees

Transaction fees are an easy way for banks to skim a little off all economic activity. Credit cards are a great business line for this reason, as many cards charge 3% from the merchant per transaction. This may seem like it doesn’t impact you as a consumer, but that 3% is baked into the prices that goods are sold at. This is one reason some stores will offer a slight discount for paying in cash.

Wire transfers, a way to almost instantly send money from bank to bank during the week, also incur a fee – usually $30 to send and $15 to receive. Sending money internationally will cost you even more, since banks usually charge a fixed fee and a ‘spread’ taken when they convert from your local currency to the currency of the nation you’re sending money to.

Some challengers are lowering these fees: tools like Venmo and Cash App (earn $5) add a simple user experience over what is essentially a bank underneath. Transferwise makes it cheaper to send money abroad through a network of bank relationships they use to minimize the actual movement of currency over borders. They charge a flat fee of around $1 and a percentage fee of around 1% of the transaction amount – which works out to be about 79% cheaper than the next best option when sending money from the UK to the Eurozone.

Bitcoin is also revolutionizing international transfers, as its unique design allows it to ignore the regulatory constraints and messy currency changes that make cross-border payments so painful and costly. With Bitcoin, the fee is based on the number of other users wanting to send Bitcoin at the same time, but currently is less than $1 regardless of transaction size. That means major savings when transferring significant sums of money – literally billions of dollars in value can be moved across any border for less than a dollar.

Account Fees

Account fees are the ‘gotchas’ of banking – overdrafts, account maintenance fees, and ATM fees are common ones in this category. Many of us are very familiar with these fees when a bill hits our account at the wrong time or we can’t find an ‘in-network’ ATM.

Overdraft fees can hit hard, with Bankrate saying the average overdraft fee is now $33.36 in the US as of 2019. This fee has climbed straight up from an average of $21.57 in 1998.

Monthly maintenance fees have also climbed, with interest-bearing accounts costing $15.05 per month on average and non-interest-bearing checking accounts costing $5.61 per month. Most banks offer to waive this fee if the customer keeps a minimum balance in their account – but minimum balances are also rising, averaging $7,123 for interest-bearing accounts and $622 for checking accounts. For young, single Americans, the average amount held in savings is only $2,729 – far below the average minimum to hold an interest-bearing account without monthly fees.

ATM fees, often charged when withdrawing money from ‘out-of-network’ ATMs, can add up to multiple dollars. On average, these fees are around $4.72 per ATM withdrawal today. That’s the highest level in 2 decades, and more than double the rate in 1998.

The final fee, which is a hidden one, comes in the form of negative interest rates. Implemented in the Eurozone for certain types of accounts and discussed in the US, negative interest rates mean depositors pay to save money. With a negative nominal interest rate, you would actually see your account balance drop over time. Today, we actually have negative real interest rates at every bank in the developed world, given that accounts earn less interest than inflation. This means your money held at the bank is actually losing purchasing power over time, even though you are lending that money to the bank so they can lend it out and earn a return on it.

Financial Advice and Wealth Management

Financial advice and wealth management involves helping clients invest their own funds. Rather than depositing funds into a bank account and earning a steady interest rate, this allows clients to take a more active role in how their funds are invested in various financial assets.

These services can also include retirement and estate planning, which involves a mix of understanding the law around finances and inheritance as well as the financial markets and asset classes.

So-called ‘robo advisors’ are beginning to chip away at this service by promising steady returns that are more reliable than those offered by a human wealth manager and higher than those offered by a savings product like an interest-bearing savings account. By automating much of the investment and money management process, robo advisors keep costs low for clients and maximize returns.

Brokerage Services

Offering clients access to financial markets is another big revenue driver for banks. Before the internet, the only way to buy and trade stocks, commodities, bonds, and currencies was through a broker who would charge a fee for executing your orders in the market.

Then came E-Trade, Charles Schwab and other online brokers who allowed people to submit orders on their own, for a small fixed fee per order of $5 or $10. Today, these incumbents are feeling the heat from challengers like Robinhood which offer ‘feeless’ stock trading on easy-to-use platforms and apps.

Mergers and Acquisitions

Branching out from retail banking, we have mergers and acquisitions consulting, which is a service many banks offer to corporations who would like to merge with or acquire other businesses. Banks help to determine the value of the companies involved in order to aid negotiations and creation of a final purchase or merger agreement. They also help the companies find financing options, since fundraising is often necessary to pull off the acquisition or merger. The fee on this service is usually some small percentage of the total size of the deal.

Restructuring

The need for a business to ‘restructure’ its finances occurs when it runs into issues paying its debts. Both the business and its creditors want to continue payments and business operations, so banks can help both parties come to agreements on how to change the debt situation to maximize value. This involves the bank making cash flow models for the business, reviewing the health of the business, and possibly helping with bankruptcy proceedings. There is usually a set fee with a percentage of the size of the asset being restructured added on.

IPOs and Fundraising

When businesses want to raise funds through an Initial Public Offering (IPO) of stock or by issuing bonds, banks can help. Through both of these processes, banks value the business and determine the structure of the financial product (equity/stock or bond/loan), then help sell that product to investors. These products are sold to private equity firms, pension funds, and other financial firms who then become investors in the business or lenders to the business. The fee on this service is usually some small percentage of the total size of the deal.

Sometimes banks will take some risk in these deals beyond simply providing advisory services for a fee, by buying and reselling the equity or bond. For example, a bank may help with an IPO by agreeing to buy 100,000 shares from the business for $14 each, because the bank believes it can sell those shares for $16 each to investors in its network.

That wraps up 12 ways banks make money. However, many of these revenue sources require that banks get their hands on a large amount of reserves so that they can fund the many loans and investments they want to make. Deposits are one way to receive funding, but there are other, often overlooked ways that banks can grow their reserves.

3 Types of Funding for Banks

The largest revenue stream for banks – lending, which makes up 59% of bank income according to Ernst & Young – requires banks to acquire funds to loan out. In our fractional reserve banking system, these funds are held as reserves that must make up a percentage of their total assets – outstanding loans and investments. This percentage is usually 10% for most banks. A reserve requirement keeps greed in check by putting a cap on how much credit a bank can extend and how many investments they can make.

Without a reserve requirement, bank employees who are compensated on the basis of the volume of loans they extend or investments they make would have no limit on the credit they could create. If a bank creates too much credit, there are too many claims on its scarce reserves and its risk of failing due to a bad loan or investment increase greatly.

The easier it is for banks to get funding, then, the easier it is for them to take more risks by extending more credit. Banks have several ways of raising funds to satisfy their reserve requirement:

- Customer Deposits

- Wholesale Debt

- Interbank Lending

Customer Deposits

Customer deposits are checking and savings accounts held by people and businesses. Many of these accounts in developed countries are insured at a federal level so that even if the bank goes bankrupt, the customers will receive their currency back. Deposits make up 78% of the average bank’s total funding, according to Ernst & Young.

Wholesale Debt

Wholesale debt involves non-deposit loans to banks, such as purchases from investors or bond offerings by the bank. This debt costs the bank a certain interest rate similar to customer deposits. These debt offerings are not protected by deposit insurance in the same way as customer deposits, and are more volatile for the bank as a funding source than deposits. Wholesale debt makes up 11% of the average bank’s total funding, according to Ernst & Young, with that number spiking to 18% for banks focused on trading and investment.

Interbank Lending

Interbank lending refers to loans from one bank to another, usually to cover reserve requirements for a very short amount of time – even a single night. These loans were often unsecured before the financial crisis, but since then they are often secured by high-quality collateral like government debt (Treasuries, in the US).

This is a very important market for monetary policy: central banks intervene in this ‘repo market’ to extend credit to banks in order to manipulate the interest rate for these overnight loans, which then affects the interest rate for all other financial products offered by the bank. The target rate set by the central bank is known as the Fed Funds Rate in the US, LIBOR in the UK, and Euribor in the Eurozone.

Central banks are unique in this market because they can create reserves and loan them to member banks – there is no limit on their ability to print currency and flood the financial system with it.

This leads to a situation where banks are incentivized to take more and more risks, because they are confident that central banks will intervene to extend them the reserves they need. Due to the financial crisis of 2020, the Federal Reserve also eliminated the 10% reserve requirement in the US, meaning that American banks are no longer required to hold any reserves to back up their deposits. The limits on their lending, investment, and trading activity are practically nonexistent.

3 Primary Banking Business Models

Despite all the ways banks are able to earn profits, most fit into a few categories due to regulatory constraints and synergies across business lines. The Bank of International Settlements identified three key models from data on income and funding sources:

- Retail-Funded

- Wholesale-Funded

- Trading Banks

Retail-funded banks are the types of banks we store our paychecks in – largely funded by customer deposits that are federally-insured, these banks make most of their profits by extending loans to individuals and businesses. This includes small community banks up to global megaliths like JP Morgan Chase.

Wholesale-funded banks similarly receive most of their income from loans, but rely more on interbank lending and wholesale debt to meet their reserve requirements. The Bank of International Settlements report notes that banks often transition between retail and wholesale-funded business models depending on the larger state of the economy – when times are good, wholesale funding can often be a faster way to grow reserves (and thus credit extension and profits) than new deposits.

Trading banks are characterized by their focus on investments and trading in equities, bonds, and commodities while taking funding from the wholesale debt markets and equity investments in their own firm. These banks are akin to hedge funds or private equity firms in many cases.

All three of these bank types may also engage in services and collect fee revenue depending on the needs of their main customer base – for example, retail-focused banks may offer more wealth management services while trading banks may focus on IPO advising or debt restructuring services.

Banking, in Summary

Banks are simply financial intermediaries that connect savers with borrowers using business expertise. However, they are so integral to our monetary system today – with a large role in creating currency through lending and storing the capital of individuals and businesses – that they operate as hybrid entities that are allowed to profit privately while socializing their losses.

This is the meaning of ‘too big to fail’ and the inherent problem of a centralized monetary system like we have today, where a small group of financiers and politicians control the ability to create currency at will. A banking system based on sound money like gold or Bitcoin has a sane, free market interest rate and a banking system regulated by the natural desire for businesses to survive and grow – instead of an addiction to free money from central banks.

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.