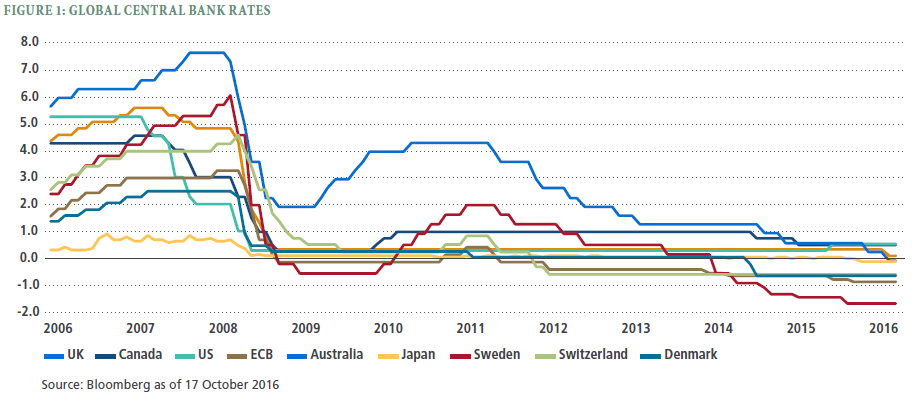

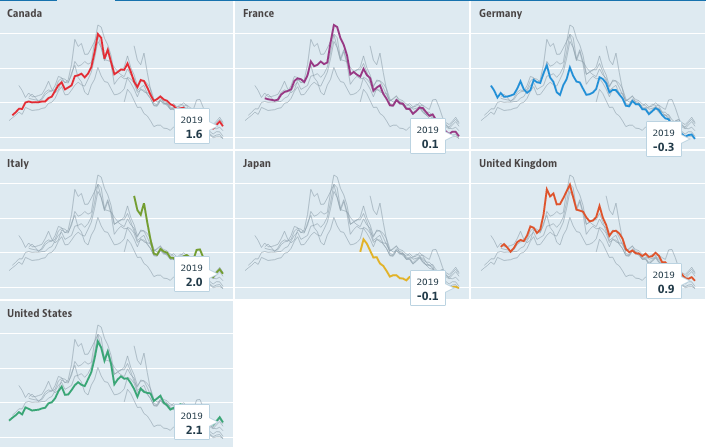

In today’s world, when a government decides it wants to stimulate its economy, the central bank of that country often lowers interest rates to make borrowing money cheaper and saving money less attractive. Interest rates have trended down in many developed economies since the middle of the 20th century, and have now passed a critical juncture in many nations: negative rates. This means central banks, which mostly trade the debt of their governments for newly printed cash, are pushing interest rates below zero.

Negative interest rates on government debt are a sign of desperate times in the global monetary system. The implication – that governments are now paid to borrow money, and savers are charged – reverses basic economic common sense. This move accelerates the debasement of currencies and suggests that savers should look for ‘safe haven’ assets that cannot be debased.

Negative interest rates are a tough beast to understand, as well as their close relationship with government debt. Unfortunately, most publications that write about these topics speak solely to an audience of financiers, so they fail to cut through the technical jargon and explain what is really going on. That is the purpose of this piece – to lay out the bare truth and present possible paths forward.

What are negative interest rates?

An interest rate can be thought of as the cost of borrowing money. In return for letting a borrower take cash from a lender, the lender will ask for the borrower to pay an interest rate. This essentially covers the ‘opportunity cost’ of the lender investing that money elsewhere, as well as the risk that the borrower doesn’t pay back the loan.

In a normal world, interest rates are always positive – this follows from the common sense law that people value things more in the present than in the future. You would not loan someone $100 of your hard-earned money just to get $98 back in a week.

Yet this is exactly what negative interest rates mean. On a loan or debt security with a negative interest rate, borrowers are essentially paid to borrow money, while lenders are charged to loan out their money.

Where do negative interest rates exist?

Negative interest rates can exist in any scenario where a loan (and corresponding debt) are created. One such scenario is with government debt, the focus of this piece.

After the 2008 recession, many central banks found themselves needing to move interest rates into negative territory because zero interest rates were not having the desired effect of reviving their economies and markets.

How can government bonds carry a negative interest rate?

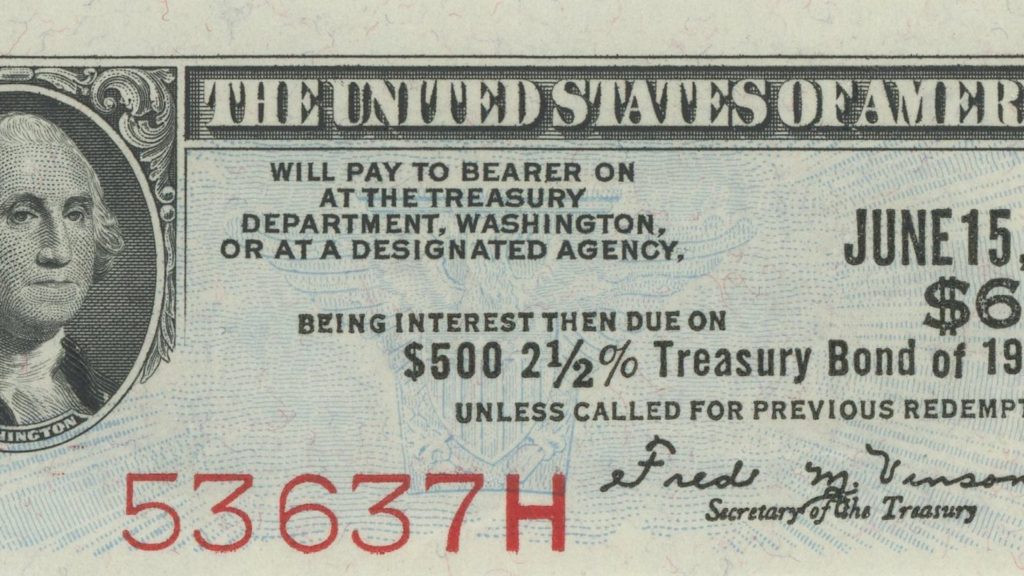

Government debt is packaged and sold in the form of bonds. Bonds are a bit different from the simple case of a loan between a borrower and a lender. Normally, buying a bond involves trading cash to the bond issuer in exchange for a piece of paper (‘bond’). The bond entitles the bondholder to ‘coupon payments’ at an agreed-upon ‘coupon rate’ over the term of the bond, with a full payment of the bond’s ‘par value’ paid to the bondholder at a certain date when the bond reaches ‘maturity’.

However, bonds trade on an open market, so prices of bonds vary depending on supply and demand. Bonds can be bid up so high that even the coupon payments plus the par value payment at maturity add up to less than the initial purchase price paid for the bond. The bond therefore has an effective ‘negative yield’ or negative interest rate.

When demand for buying bonds is higher than supply of sellers of bonds, the price of bonds goes up while the yield goes down. The opposite occurs when demand is lower than supply.

Let’s look at an example:

- You buy a 1 year government bond on the open market, where it is trading for $1,235. This bond has a par value of $1,000, meaning it pays out $1,000 at maturity (in one year). This bond carries a 2% annual coupon rate.

- Over the course of the year, you receive $20 in coupon payments (2% * $1,000).

- At the end of the year, the government pays you the par value of the bond: $1,000

- So, at the beginning of the year you paid $1,235 to buy the bond. At the end of the year, you have $1,020. You lost $215 on this bond because it had a yield, or interest rate, of -17%.

If a bond buyer loses money holding a bond until maturity, why is nearly $14 trillion in debt carrying a negative interest rate today?

Some economists spin this strange situation by saying it’s simply a ‘storage fee’ that bondholders must pay so that central banks and governments can hold the bondholder’s cash. However, this ‘storage fee’ only exists because of central bank actions – let’s examine.

How do central banks make government bonds earn a negative interest rate?

As stated earlier, bonds trade on an open market based on supply and demand. The interest rate, or yield, on the bond varies with the price of the bond, which varies with supply and demand.

Bonds are bought and sold with cash, or in financial parlance, ‘base money’ – think of this as cold, hard US dollars, Euros, or another major currency. Most buyers in the bond market have a limited supply of this cash and can’t create more of it. However, central banks can create more cash, whenever they want.

By creating cash at will, central banks can always buy more bonds. The main bonds most central banks buy are the bonds of their governments. Central banks like the Fed are lending newly printed cash to their government with each bond purchase. This allows the central bank to manipulate interest rates to a ‘target’ rate. In the United States, this is known as the federal funds rate, and the Fed will say something like “we want to target a federal funds rate of 25 basis points.” This means that the Fed wants to buy and sell government bonds so that the interest rate on those bonds works out to be about 0.25%.

To push the interest rate into negative territory, a central bank just needs to print a ton of cash and buy up government bonds with it, thereby extending loans to the government and lowering the interest rate. All interest rates in an economy, from mortgages to corporate bonds, are impacted by the change in this key government debt interest rate.

When this rate goes negative, we can say that government debt is earning a negative yield or that central banks are charging commercial banks for reserves parked at the central bank. These two are used interchangeably in financial publications, which can make it difficult to understand what is really happening.

These two things are one and the same – a commercial bank is ‘parking reserve cash at the central bank’ when it buys a government bond from the central bank. The commercial bank may trade that bond back for cash the next day if the transaction is part of a very common short term or ‘overnight’ loan. If that government debt earns a negative yield, the bank will receive back less cash than it initially spent to buy the bond.

Here is the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank of the United States explaining how lending between the central bank (Fed) and commercial banks is tied to government bond yields, or interest rates:

“In general, the overnight lending rate on loans and deposits from a central bank to commercial banks is called a policy rate. In the U.S., this rate is the federal funds rate. This overnight lending rate is a key economic tool for central bankers as it can be used to adjust the cost of borrowing, which influences real economic activity. For example, since the Fed’s lending (or deposit) rate directly translates into short term government bond yields (e.g., through open market operations), low interest rates incentivize others to shift investment from low-yielding government bonds to more productive investments.”

St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank of the United States

Why do central banks push down the interest rate on government debt?

Central banks are pushing interest rates on government debt in to negative territory for three main reasons:

- Belief that lower interest rates spur lending and spending, and thus economic growth

- Belief that spurring spending will help avoid a ‘deflationary spiral’ where prices fall, causing more savings, which causes prices to fall further

- Desire to debase their own currency in order to make their nation’s exports cheaper in the international market

Central banks have pursued these goals from time to time over the past several decades by lowering interest rates. However, the market always adapts to the new, lower rates, meaning even lower rates are needed during the next economic slowdown or trade trouble in order to get the same desired effect. Thus, interest rates in all developed countries have steadily trended down since the global gold standard ended in 1971.

What does negative-yielding government debt mean for you?

Negative-yielding government debt is an abstract concept for many of us because it doesn’t seem to touch our everyday lives. However, when we consider that all interest rates in an economy are influenced by the yield, or interest rate, on government debt, we can start to see how this rate might be important to understand.

Unfortunately, a negative interest rate on government debt doesn’t mean you’ll be paid to take out a mortgage. The bank still needs to make a profit, and the risk a bank takes lending to you is far higher than the risk they take lending to the government – even if the latter has a small guaranteed loss.

Sapping your savings with a ‘storage fee’

However, a negative interest rate could be passed on to regular people another way – through a ‘storage fee’ on bank deposits. Commercial banks who feel the squeeze on profits caused by negative-yielding government debt may decide to charge fees or interest on the money you deposit in the bank. They would justify this by touting the services they provide – whether that be foreign exchange, money management, budgeting software, or stock trading.

This isn’t so far fetched if we consider the fact that today’s bank accounts actually have a negative real interest rate – because of inflation, the cash you hold in a bank is losing value over time. In a world without central banks pushing down interest rates with newly printed cash, you would earn a small return over time by lending your cash to the bank in a savings account.

The central bank may also directly impose negative interest rates on the savings of regular citizens through a ‘digital dollar’ where citizens have bank accounts at the central bank, instead of a commercial bank.

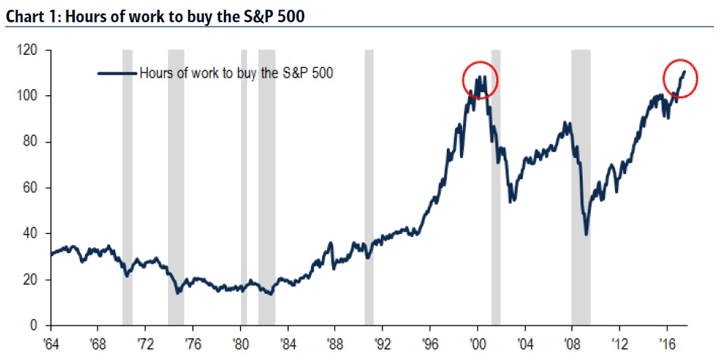

Reducing your wage through currency debasement

Another way negative interest rates (and low rates) affect you today is by lowering the real purchasing power of your wage. Since wages and salaries are fixed to a certain value in currency, they only slowly adjust to inflation in both consumer goods prices and savings instruments like stocks and bonds. Retirees suffer the most, as their income is fixed. The result, which can be hard to observe day to day, is that the things you buy to live and save rise in price faster than your income.

The wealth you’re losing doesn’t disappear however – so where does it go? It is transferred from savers to borrowers. Who are the biggest borrowers? Governments and large corporations, which have grown their debts steadily for the past 70 years.

Banks, however, have adapted to this world by reducing lending and increasing speculation in the bond market. As intermediaries, they are neither lender nor borrower – they are simply moving money from lenders to borrowers.

Banks can therefore earn a profit in a negative rate world by speculating on bond prices. Since central banks implement negative rates by buying up government debt, banks buy bonds when they expect central banks to buy them, so they can sell them at a profit when the price increases. Central banks are thus inflating a bubble in sovereign (government) debt – as JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said in early 2020. This creates systemic risk not only to the financial system, but to our monetary system and the value of our currency. That could have major ramifications on your savings, job, and livelihood.

What can you do about negative interest rates on government debt?

Negative interest rates cause a slow drain on the wealth of savers and present a systemic risk to the value of our currency. So how can you protect against this drain and risk?

The best way to protect yourself is to opt out of the financial and monetary system which feeds off pumps in asset prices caused by negative rates and other central bank ‘liquidity’ measures like quantitative easing. Issuers of financial assets, and creators of investments (think entrepreneurs and real estate developers) respond to the increased liquidity created by central banks by increasing supply of whatever they produce. This allows them to capture more of the newly printed cash coming out of central banks – more profit. So we see more startups raising insane amounts of money with no business fundamentals, skyrocketing housing markets with empty homes, and big corporate bond sales.

Opting out of the traditional system doesn’t mean quitting on life and moving to a deserted island. What it does mean is shifting your savings out of the traditional system. The good news is you are early in detecting this trend – so you don’t need to move 100% of your savings. Even 1% or 5% is enough to provide some protection.

What does it mean to ‘shift your savings out of the traditional system’? Instead of holding fiat currencies like dollars or buying stocks, bonds, and other assets that increase in supply regularly, buy assets with limited supply. You may think there are many assets like this, but in fact there are very few – with the two most notable being gold and Bitcoin. Gold and Bitcoin have proven themselves over time to be very difficult to produce, making them sound money that will hold value in terms of the goods and services they can buy over 5+ year periods. While they may fluctuate wildly within the span of a few years, both of these assets have undeniably increased in purchasing power over 5+ year periods.

Governments will have a hard time implementing negative rates on your gold or Bitcoin if you hold it yourself, rather than keeping it in a bank. That’s a good thing for you, your family, and your future.

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.