Currency in the United States went through many forms before the ‘fiat’ dollar we have today. In this post, I’ll cover how 7 major events changed the US dollar and led us to the monetary system we have today.

In broad strokes, the US dollar began as a way for the colonial governments to raise funds for military expeditions and eventually a war for independence from Britain. Through much of the 19th century, the official US dollar backed many paper currencies produced by banks. After the Civil War, the US government discouraged private issuance of paper banknotes and consolidated currency issuance under a national system of banks.

The US dollar rose to world prominence after two world wars, which devastated the dominant European countries and led to a centralization of gold, the main store of value and true ‘money’ of the day, in the United States. Then, in 1971, the world suddenly shifted back to a place governments usually only went during crises and wartime – a completely fiat currency, essentially holding value due to the faith that governments will continue to effectively collect tax and enforce the use of that currency.

Let’s dive in to the 7 events, which are:

- American Revolutionary War

- Coinage Act of 1792

- National Banking Act of 1863

- Coinage Act of 1873

- Federal Reserve Act

- 6102 and Gold Reserve Act

- Nixon Shock of 1971

American Revolutionary War – Funding the Revolution

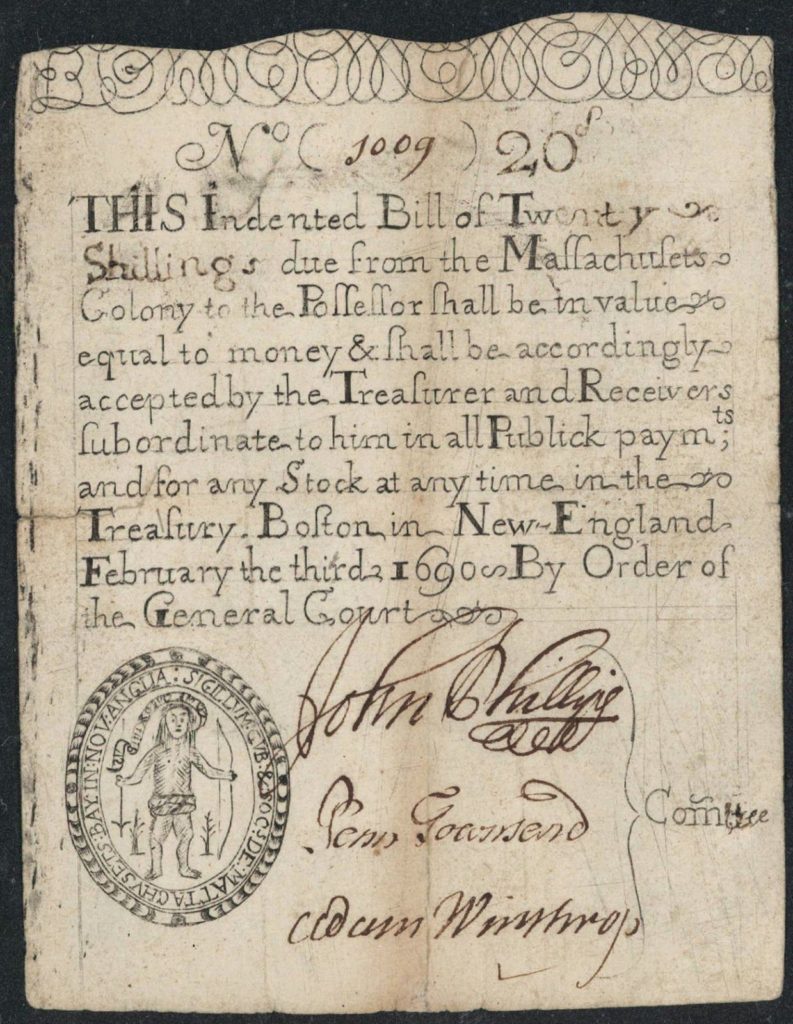

Prior to the Revolutionary War, the colonies in America mainly used silver and gold pieces from Europe as the primary medium of exchange – especially the Spanish ‘piece of eight’ silver coin, or ‘Spanish dollar’. Colonial governments had occasionally sold paper ‘bills of credit’ in exchange for European coins made of gold or silver, labor, or goods in order to undertake military expeditions. These bills would also circulate along with metal ‘specie’ or coinage like the Spanish dollar. The first of these currencies was printed in 1690 by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in order to finance a military expedition into Canada.

When the Revolutionary War began, the newly created Continental Congress needed funding to pay for the war, so they circulated the first American national paper currency – the Continental. However, the precious metals to back this currency at face value never came into the government’s possession, and it was severely devalued – losing 97.5% of its value over 5 years.

Following the war, the American populace felt burned by paper currency and no longer trusted when the government attempted to print and circulate paper. The government had used this currency to essentially borrow for free from the American people, since the government could print it for virtually no cost while the people accepted it in exchange for valuable goods and services.

The government needed a new plan, and with the adoption of the Constitution came a commitment to sound money – in Article 1, Section 10 the Constitution states that “no state shall emit bills of credit (paper currency) or make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts.” There was no provision for the federal government to ‘emit bills of credit’ – only to ‘coin money’. At that time, ‘bills of credit’ was the standard term for paper currency, while ‘coin’ meant to turn silver and gold into coinage.

The Coinage Act of 1792 further cemented the role of precious metals, and their all-important natural scarcity, in the monetary system of the United States.

Coinage Act of 1792 – A Process for Minting Sound Money

Following the chaos of wartime finances, the first US administration under George Washington’s leadership wanted to create a stable unit of account and medium of exchange for the country. The Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, advised Congress on a piece of legislation titled An act establishing a mint, and regulating the Coins of the United States.

This became known as the Coinage Act of 1792, and it created the first official United States dollar, a silver coin named as such because it was modeled after the Spanish dollar and held the same quantity of silver. The Act also provided for the creation of a United States Mint, tasked with creating and verifying coinage, and a decimal system of currency.

Beyond the silver dollar were half dollars, quarter dollars (quarters), dismes (dimes) and half dismes (nickels). There were also gold coins – the $10 eagle, $5 half eagle and $2.50 quarter eagle – and copper cents ($0.01) and half cents ($0.005). The Mint maintained a standard purity of the metal in each coin, ensuring that the coin was a fair representation of a scarce commodity – gold or silver. The government nor banks were able to produce more gold or silver coins at will, like they could with paper currency.

The Coinage Act also allowed anyone to bring bullion (blocks of gold or silver) to the Mint and receive an equivalent value of coin in return, free of charge. In this way, US currency was nothing more than an authenticated piece of silver or gold. The inscriptions on the coin basically meant that a large entity – the government of the United States – vouched for the purity of the metal in the coin.

However, paper currency would return – but not from the government’s printing presses (yet).

National Banking Act of 1863 – Centralizing Banking

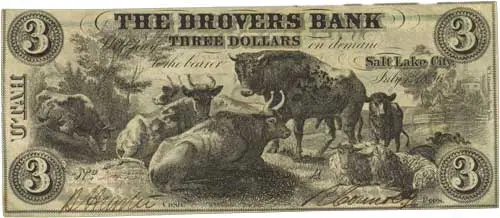

The period from 1837 up to the Civil War was known as the Free Banking Era, because many banks began to issue their own banknotes against the gold and silver coins in their vaults. Each note was redeemable for a fixed amount of coinage. Light regulation by states and a need for more physical currency to circulate was a dangerous combination, leading many banks to create far more banknotes than they had coins to back.

From 1797 to 1837, the number of state-chartered banks ballooned from 24 to 712. Banks often failed during this period due to ‘bank runs’. A bank run occurs when more banknotes are circulating than the bank has to back them all. This works as long as too many people don’t come to redeem their notes for coins – but if enough people come to redeem, the bank runs out of coins and has to shut down, leaving those still holding banknotes with worthless pieces of paper. This is a ‘bank run’.

During the Free Banking Era, the sheer multitude of currencies circulating and shakiness of the banks that backed them led to massive increases and decreases in the currency supply, and therefore fluctuations in the prices for goods and services.

The beginning of the Civil War brought the end of this era with the passing of the National Banking Act of 1863. This act provided loans to aid the Union in the Civil War and set up a system of national banks held to higher standards than the state banks that proliferated during the Free Banking Era. These national banks were mandated to accept each other’s paper currency at face value, and a new office called the Comptroller of the Currency ensured all notes were of uniform quality – these notes were known as ‘greenbacks.’

This office was similar to the Mint, but instead of creating coinage, it created paper currency that represented a claim on US government debt, known as ‘Treasuries’. Just as the fledgling colonial congress did to finance the Revolutionary War, the Union government was essentially selling their debt to the people and calling it currency, or money.

The government declared these notes ‘legal tender’ – meaning creditors were legally obligated to accept them as payment to settle debts – ensuring they would be used in commerce and retain their value. The Union, of course, won the war and the currency survived, eventually returning to a gold-standard system where all circulating national currencies could be redeemed for gold.

Coinage Act of 1873 – No More Silver

Since the Coinage Act of 1792, the US was on a ‘bimetallic’ standard that tied both silver and gold’s value together to the ‘dollar’ system. However, this presented problems when the relative values of silver and gold fluctuated on the open market. Both silver and gold have other uses – industrial and jewelry being two – and occasionally supply changes of one or the other would cause the relative values to change drastically.

Since the dollar system pegged the values of gold and silver against each other, with 5 silver dollars equal to one gold half eagle, for example, there was a profit opportunity here. When silver was overvalued versus gold, holders of silver coins would sell them to manufacturers and jewelers for gold and then buy their silver coins back at face value, pocketing the difference. When silver was undervalued versus gold, holders of silver would take their metal to the Mint to have coins made – instantly raising the value of their silver.

The Coinage Act of 1873 ‘demonetized’ silver, ending the ability for silver holders to go to the Mint and have fully legal tender coins made from their metal. This Act hurt many silver producers in the Western United States, like those mining the Comstock Lode, by devaluing silver itself. The act also reduced the currency supply, raising the value of each unit of currency in circulation and thus hurting many farmers and others who carried a lot of debt. Suddenly it was more expensive for debtors to acquire the currency they needed to pay down their debts.

The reduction in the currency supply may have helped set off the Panic of 1873, which ended a period of economic overexpansion and a railroad boom.

The battle to remonetize silver waged for several decades after the Coinage Act of 1873, with minor victories for silver holders such as the Bland-Allison Act of 1878 that required the US Treasury to purchase millions of dollars’ worth of silver each month and mint silver dollars with it. However, silver was on its way out and eventually the country officially went on to a gold standard in 1900 with the Gold Standard Act.

However, by the late 1800s 90% of the currency supply was held in checking accounts at banks. Paper currency and bank accounts had begun to drive out the everyday usage of coinage.

Federal Reserve Act – Centralizing Banking, Round 2

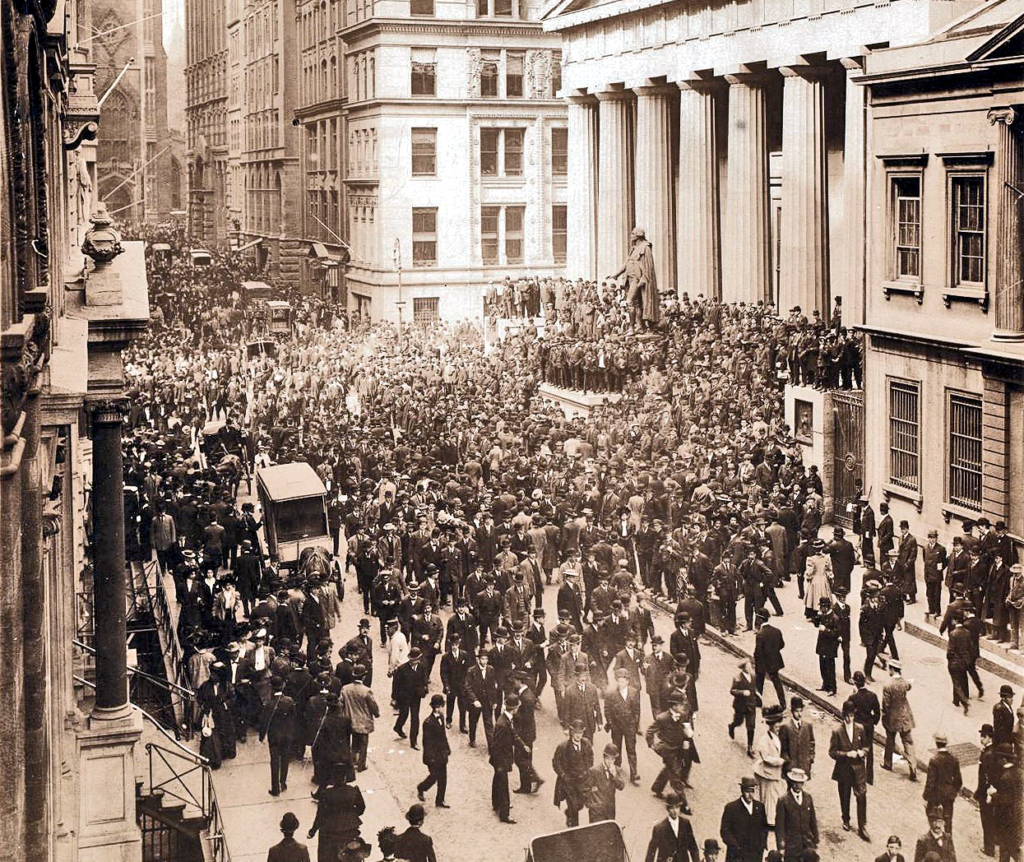

Overextensions of credit came crashing down in the Banking Panic of 1907, which threatened to throw the economy into a depression. Wall Street financiers, led by J.P. Morgan, met in the Morgan mansion in New York and decided to use their capital to float the failing banks, and thus float the entire economy surviving on bank credit.

Out of this panic, the federal government became involved and started planning for a central bank modeled on European nations like Britain and Germany. This went against the founding ideals of the nation, which was created in reaction to the centralization of monarchical European powers and therefore prized decentralizing power and responsibility in states, localities, and private banks.

However, the banking panic and the bankers that went through it convinced the federal government to create a central bank for the nation. This bank issued paper currency which represented claims on gold at the Treasury. It would also have the ability to purchase government debt (‘Treasuries’) with newly printed paper currency, thus increasing the currency supply. This action is known as Open Market Operations. This was meant to help stabilize the economy during panics, when credit bubbles were unwinding and it seemed as if the economy was “low on liquidity” or simply needed more dollars to continue functioning.

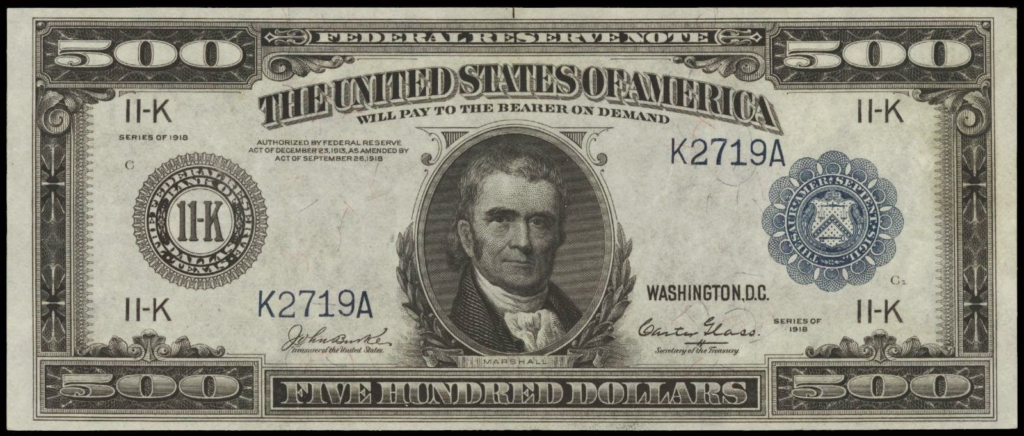

The Federal Reserve printed Federal Reserve Notes, which looked very similar to the dollar bills we use today. However, these bills were “as good as gold” – meaning they were claims on gold held at the Treasury, and traded at an equal value to the gold they represented. Each dollar was worth about 1.5 grams of gold.

However, the Federal Reserve also bought Treasuries with newly printed dollars, diluting the value of the dollar without changing the official amount of gold it was redeemable for. This creates an expansion of credit in the economy and leads to inflation – although sometimes that inflation does not occur within the narrowly-defined Consumer Price Index (CPI) that we today think of as inflation. This dilution also created an incentive for citizens to claim gold with dollars, since the dollars were oftentimes worth less than the gold they represented.

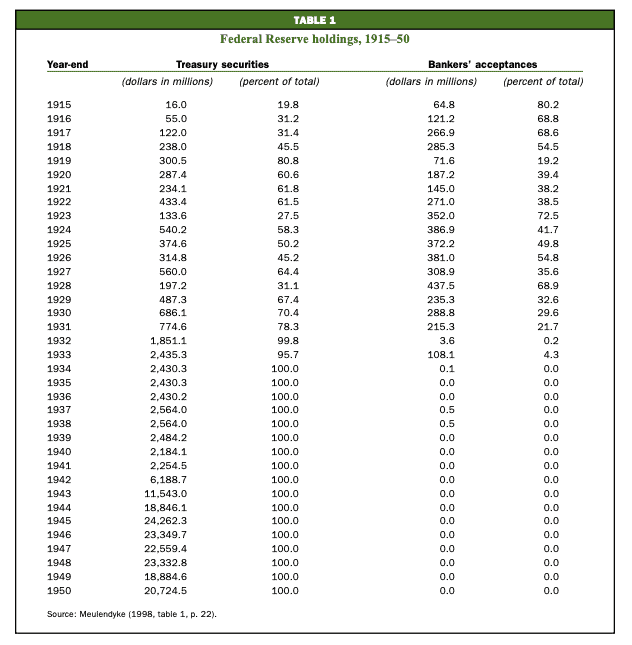

Over the late 1910s and 1920s, the Federal Reserve transitioned from holding mainly short-term debt known as bankers’ acceptances to long term Treasury securities, violating the common sense ‘real bills doctrine’ that many economists believed in that day (download: page 4, Table 1 – also below). The real bills doctrine discouraged central banks from buying long term debt that would expand the currency supply for long periods of time, preferring short term debt that allowed short shocks in the market to be smoothed over.

When the currency supply expands massively, speculation runs rampant. In 1929, this massive speculative bubble collapsed, leading to the Great Depression.

6102 and Gold Reserve Act – Dollars are not “As Good as Gold”

By 1933, the Great Depression and monetary debasement by the Federal Reserve left the bank and the government in a difficult position. The Federal Reserve Act mandated a 40% gold backing of all Federal Reserve Notes in circulation, but they were running close to that limit.

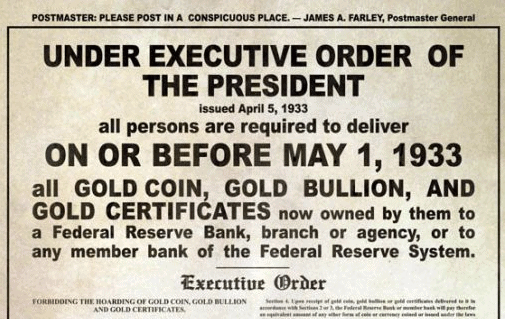

On April 5th, 1933, FDR signed Executive Order 6102, which required all Americans to deliver any and all gold they owned, except a small amount of coin, to the Federal Reserve. The deadline for doing so less than one month away – May 1st. Americans received the official amount of gold for each dollar at a rate of $20.67 per troy ounce of gold.

Less than a year later, FDR signed the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, which transferred all gold held by the Federal Reserve to the Treasury, prohibited the Treasury and banks from honoring the redemption of dollars for gold, and allowed the President to revalue the dollar on the international market to $35 per ounce of gold. While this all may sound very technical, the result was transfer of the gold reserves of American citizens to the US government, followed by a devaluation of the dollars which the government ‘traded’ to their citizens in exchange for the gold.

Preventing further redemption of dollars for gold set the stage for a future in which the Federal Reserve and US government could continue to debase the dollar by printing more. After the 1929 crash, citizens were able to protect their savings from this debasement by claiming the gold they were owed. No redemption meant the government could debase the dollar without fearing that their citizens would drain the government’s coffers of an actually scarce asset: gold.

Nixon Shock of 1971 – Beginning the ‘Fiat’ Era

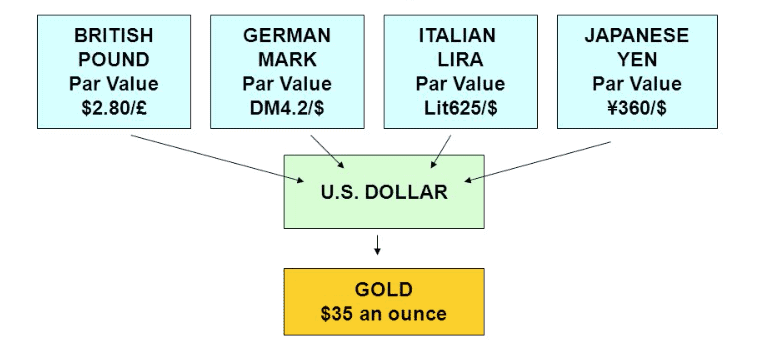

After WWII, the US set the rules with the Bretton Woods monetary system. While this did not change the dollar domestically, it had major ramifications across the globe that affected Americans.

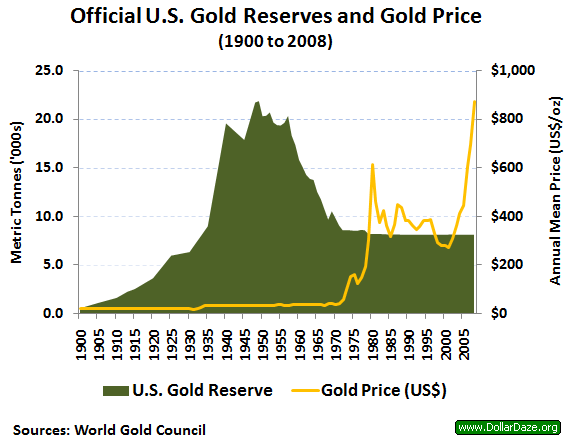

The Bretton Woods system tied all global currencies to the dollar at fixed exchange rates. The dollar was then fixed to gold at $35 per ounce, and foreign central banks were allowed to redeem their dollars for gold at that rate. At this time, the US held most of the world’s gold supply.

However, to fund social programs and the rising costs of various wars (most notably, the war in Vietnam), the Federal Reserve bought large amounts of Treasury securities and handed the government freshly printed dollars. As those dollars circulated, the value of the dollar decreased to a point where one troy ounce of gold was actually worth $200 if dollars were fully backed by the gold held by the US Treasury. A far cry from the stated $35.

Nations realized this, especially France, and began redeeming dollars for gold – which only worsened the situation by reducing the gold holdings of the United States and further devaluing the dollar.

Charles DeGaulle Calls the USA’s Fiat Currency Bluff

In 1971, without much fanfare, President Nixon announced that the US government would no longer allow foreign central banks to redeem dollars for gold. Since all foreign currencies were also tied to gold only through the dollar, this effectively made all major currencies ‘fiat’ in one fell swoop.

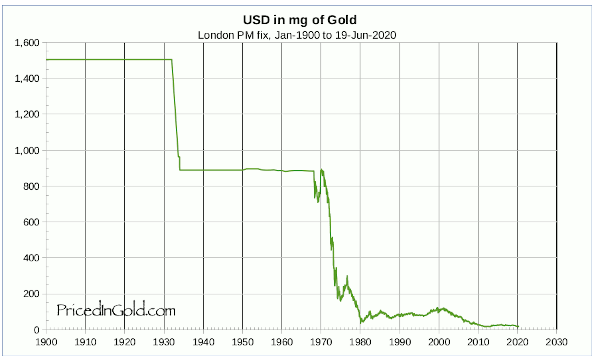

The massive debasement of the dollar over the past 25 years came out violently in a massive crash in the value of the dollar against gold. Long held at $35 per troy ounce of gold officially, the free market began to understand and reflect that there were far too many dollars in circulation against gold to back them.

The price of gold in dollars (the inverse of the chart above) went from $35 per troy ounce of gold to over $600 in 10 years.

While this might look like a bubble in the price of gold, we actually don’t see the gold price ever returning to levels near $35 per ounce. Rather than a bubble in the price of gold, this chart can be better understood as the world realizing that the value of the dollar is no longer tied to a scarce commodity, but to beliefs about the stability of the US government and its power over other nations. That belief is steadily waning, exacerbated by constant deficit spending and monetary policy measures causing a massive expansion in the supply of US dollars.

Today’s Dollar

The dollar has now returned to a state of being a ‘bill of credit’ like those issued to fund the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. Each dollar simply represents credit put forth to the United States federal government, which then spends that credit wherever it sees fit.

However, we still think of the dollar as something like gold – a store of value and a scarce asset. In fact, it is a terrible store of value by design, and performs worse when more stimulus is printed, the federal debt enlarges, or the Federal Reserve pushes interest rates lower.

The dollar bill (and the dollar digits in your bank account) are now credits created by the US government or a major bank, and put into circulation through the extension of a loan or as payment from the government for work done, benefits, bailouts, etc. New dollars are created when major banks make loans, or the Federal Reserve buys US Treasuries. Both actions involve simply ‘marking up the account’ of a bank or individual. The government promises to repay their debt later, but they can pay it back by printing more dollars in exchange for more debt – similar to a Ponzi scheme.

Just like banks were able to create currency during the Free Banking Era, banks can do the same today – but only a chosen few which are sanctioned by the government. These banks are strange businesses because they are entirely private, with shareholders who get richer when the banks are growing. However, when the banks fail, they are deemed ‘too big to fail’ by the government, and the Federal Reserve steps in to ultimately save a private business from failure. In the end, the shareholders profit from success while being insulated from failure. This is the result for any business that receives a ‘bailout’ from the government.

Today’s dollar requires trust – trust in the banks, the Federal Reserve, and the federal government to do what’s in our best interest with their significant power to create currency out of thin air. Unfortunately, history tells us that this trust is often misplaced, and ends in significant transfers of wealth from hardworking populations to bureaucrats in power.

The future of the dollar is uncertain – it faces threats from other nations and free people, but the US government still has a few moves it can play to prolong the dollar’s lifespan.

If you like my work, please share it with your friends and family. My goal is to provide everyone a window into economics and how it affects their lives.

Subscribe to email updates when new posts are published.

All content on WhatIsMoney.info is published in accordance with our Editorial Policy.